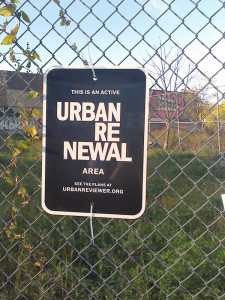

Municipalities have been overtly abusing the broad authority given them under Colorado’s urban renewal law for decades. What was originally intended to address the problems stemming from people living in sub-standard housing amidst squalor is now almost exclusively used by politicians and planners to give public subsidies to private interests for preferred economic development projects. So it is significant that on July 5, the Littleton City Council is scheduled to vote on an ordinance to repeal that city’s urban renewal authority (URA). While voters have been pushing back on URA abuse at the ballot box, for a city council to legislatively repeal an ongoing URA would be hugely beneficial to both local and state taxpayers, and set an important precedent for other cities to follow.

The legislative declaration in Colorado’s urban renewal law (CRS 31-25-102) makes clear the reasons for granting sweeping power to URAs is because there exist “slum and blighted areas” in municipalities that constitute a “serious and growing menace” to the public health, safety, morals and welfare. That unaddressed these areas would contribute substantially to “the spread of disease and crime.” That municipalities must not continue to be endangered by areas which are “the focal centers of disease” and “promote juvenile delinquency,” and which consume an “excessive proportion” of government revenues.

Colorado’s declaration is patterned after the Federal Housing Act of 1949. Both federal and state laws sought to address the threats that come from people living in substandard housing amidst squalid conditions. The words “disease” and “crime” were not used by accident. Diseases and crimes are what make slums and blighted areas a matter of statewide interest, and warrant the state government enabled response delegating the power of property tax diversion and condemnation to municipalities.

Colorado never really had the slums of the big eastern cities, so our problem with slum and blight was not as large as other states. But the reality of today is that slums, which breed disease and crime, and pose an imminent threat to the state in general, do not exist in Colorado. This should be a cause for celebration and an end to the slum and blight elimination programs.

But when federal funds had effectively dried up by the 1970s, no victory over slum and blight was declared. Instead, advocates of a government planned future switched to Tax Increment Financing (TIF) to fund URAs.

TIF is a diversion of tax revenues to repay bonds that are issued to subsidize a government desired development on a specific site. The money that funds TIF, the increment, is the difference between the taxes collected before development on a specific URA site as compared to the taxes collected after development. The diverted tax dollars are siphoned off from other local governments such as school districts and special districts. State taxpayers are asked to “backfill” the lost schools revenue. The backfill is now about $40 million a year state-wide.

Research has shown that TIF doesn’t actually lead to new development, but rather subsidizes development that would have taken place anyway, just in another place and time. All TIF does is influence the location and perhaps the form of that development. Economists Richard Dye and David Merriman looked at property value growth rates for 235 northeastern Illinois municipalities, where about 1/3 of those municipalities had adapted the use of TIF. After controlling for sample-selection bias (cities that were already growing and TIF was introduced to capture a property tax-base vs. cities that introduced TIF in an attempt to spur economic growth) they found evidence to show not only that TIF areas grow at the expense of non-TIF areas, but that municipalities that adopt TIF actually grow more slowly than those do not.

In any rational review of Colorado URAs, only a handful of properties would even approach the designation of slum. Areas that would endanger the state and its municipalities as focal centers of disease, or promote juvenile delinquency, are simply non-existent.

As Littleton City Council member Doug Clark noted during an appearance on the Independence Institute’s public affairs tv show Devil’s Advocate (the show is embedded below) there are currently four different urban renewal plans in Littleton.

But it is absurd to try and make the case that Littleton suffers from four different “slum and blighted” areas that are focal points for the substantial spread of disease, crime and juvenile delinquency, or a growing menace to public health, safety, morals and welfare. In fact, as part of one of those plans, the Sante Fe Urban Renewal Plan, the city declared over 100 acres of agricultural land as “blighted” in order to bring it under the control of the URA and authorize use of TIF. In response, Arapahoe County Assessor Corbin Sakdol determined the land had been illegally included in the plan, in violation of a 2010 law passed by the legislature to prohibit inclusion of agricultural land in URAs unless very strict requirements are met. Littleton sued over the decision. On June 7, Arapahoe County District Court ruled that Littleton had indeed “blighted” the land in violation of state law.

Councilman Clark goes on to describe the designation of a new King Soopers supermarket already under construction as slum and blighted, only months before its completion and grand opening.

Littleton voters have already set the stage for their city council to act. In a March, 2015 special election, voters overwhelmingly (60-40) approved Initiative 300, a citizen-led ballot measure which requires voter approval for any urban renewal plan that utilizes TIF.

Opponents of 300 argued that if a URA couldn’t hand out TIF financing packages as they saw fit, no one would be willing to develop projects in Littleton. As the Littleton Independent newspaper editorialized at the time, “Just sending Initiative 300 to a vote of the people hurts Littleton’s image of being pro-business and a good place in which to invest.”

Yet at the April 5, 2016 Littleton City Council meeting, more than a year after passage of 300, city staff reported that Littleton’s planning and development department is “swamped” (at mark 1:03:04 in video).

The citizen pushback in Littleton is not unique. When voters and taxpayers have been given the opportunity to weigh in, they have rejected URAs and TIF.

In the November 2015 election, Wheat Ridge voters passed their own Initiative 300 as a charter amendment, stripping their URA board of TIF, cost sharing and revenue sharing discretion. Under the ordinance, any TIF over $2.5 million must now be approved by voters at the ballot. TIFs under $2.5 million must be approved by Wheat Ridge City Council, rather than by the unelected URA board members.

In 2007 the Town Board of Windsor set URA boundaries that included the main street and a proposed site for a Walmart. In response Windsor voters, encouraged by a local Fire District, abolished the URA by a margin of 60% to 40%.

In a January 2010 special election, Estes Park voters overwhelmingly (61-39) abolished that city’s urban renewal authority. The formation of new URAs in Estes Park now require a popular vote.

In early 2015, the Steamboat Springs City Council declared its vibrant, tourist-destination downtown as “blighted.” The blight designation was a necessary first step in a plan to form a downtown URA and utilize TIF for redevelopment projects. This prompted a groundswell of both public and sister governments comments. Steamboat Springs Board of Education member Scott Bideau wrote that, “Steamboat’s existing, TIF-funded mountain URA currently diverts over $400,000 per year in local property tax revenue away from the school district while also increasing property taxes outside the URA to cover the school mill levy overrides and bond payments that are not paid for by new development within the URA or backfilled by the state.”

In addition, Steamboat citizens began a petition drive to require voter approval for URA/TIF modeled after the Littleton 300 measure.

In June 2015, the Steamboat Springs City Council acquiesced to public sentiment and voted to kill the URA/TIF plan they had only months before approved.

From its origins as an effort to address legitimate slum and blight, URAs and TIF are now prime examples of cronyism and corporate welfare at the local level.

Ideally, the legislature would simply declare victory over slum and blight in Colorado and repeal the badly outdated urban renewal statute, along with all existing TIF authority. This is what the California State Legislature did in 2010, when the abuse of TIF through redevelopment authorities (RDAs) became an unsustainable burden on schools and other programs.

In the meantime, the Littleton City Council has an excellent opportunity to pave the path out of urban renewal for other Colorado municipalities

Mike Krause directs the Local Colorado Project at the Independence Institute, a free market think tank in Denver. This article was partially excerpted from a forthcoming Independence Institute Issue Paper on TIF/URA.