The United States’ traditional electric grid is an engineering marvel with nearly 160,000 miles of transmission lines, millions of miles of distribution lines, and over 73,000 power plants.

It delivers power throughout all of America, and it allows us to use air conditioners in the summer and heaters in the winter. One hundred years ago, electricity was a luxury, today, it is an affordable staple and absolute necessity to power our 21stcentury economy.

But the traditional, centralized electric grid is ripe for change. Large power plants can cost up to a billion dollars or more to build and are often located miles from population centers. As a result, transmission lines, which cost a million dollars or more per mile, must be extraneously long. In Colorado, for example, Xcel’s “Rush Creek Connect” is an 83-mile, $120 million transmission line project that connects the Rush Creek Wind Farm to the rest of the grid.

These current realities should be considered necessary evils that cost ratepayers, who in Colorado are captive customers of regulated monopolies like Xcel, millions every year.

Moreover, both regulation and deregulation has stifled innovation and failed ratepayers. The status quo is either endure an esoteric, regulated model that allows utilities to manipulate the market and gouge their customers, or live with a deregulated market that has volatile, and often, higher rates.

All the while, new business platforms like Uber and Airbnb have permanently altered traditional business models that a decade ago seemed unchangeable. Economists are calling the market where these new entities operate the sharing economy, and while it may seem impossible, its next breakout platform could be the energy sector because of microgrid technology.

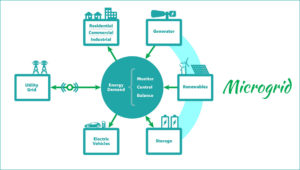

Microgrids are small electric grids that consist of generation sources, distribution lines, and control mechanisms that switch gears and regulate voltage. According to the Department of Energy, “A microgrid is a group of interconnected loads and distributed energy resources within clearly defined electrical boundaries that acts as a single controllable entity with respect to the grid. A microgrid can connect and disconnect from the grid to enable it to operate in both grid-connected or island-mode.”

Within th![]() e service area of a microgrid, electric generation is disseminated and owned by individuals and businesses. One household may install solar panels and batteries while another might utilize a diesel or natural gas generator. Regardless, because individuals own the decentralized generation sources, massive power plants and long transmission lines are rendered obsolete.

e service area of a microgrid, electric generation is disseminated and owned by individuals and businesses. One household may install solar panels and batteries while another might utilize a diesel or natural gas generator. Regardless, because individuals own the decentralized generation sources, massive power plants and long transmission lines are rendered obsolete.

Distribution lines would still be required within the “defined electrical boundary” in order to connect the participants, but without the need for large power plants and long transmission lines, infrastructure costs would most likely drop.

From powering prisons to college campuses to neighborhoods, microgrids enable communities to be independent from central electric utilities. They’re powered by a variety of sources (generators, batteries, solar panels, etc.) and are self-sufficient systems that can act in parallel with the central grid or function autonomously.

Fort Collins is already experimenting with microgrid technology, and in the future, it is hoping to produce as much energy as it uses. Thus far, New Belgium Brewery, InteGrid laboratory, City of Fort Collins facilities, Larimer County facilities, and Colorado State University main campus facilities are customer participants. New Belgium Brewery on its own can already produce over half of its needed power at peak demand. It is important to note that Fort Collins’ microgrid is considered a milligrid, because it technically operates as a segment of the city’s municipal electric utility.

In reality, though, milligrids will most likely be the next step since Colorado remains a regulated energy state — and Xcel won’t willingly give up its monopoly and guaranteed profits just because of some new technology. However, by implementing milligrids throughout the service areas of Xcel, Black Hills Energy, and municipal utilities, microgrid technology can become part of the system with the hopes of eventually replacing centralized utilities for good.

It’s Uber for Energy, or the power sectors’ neighbor-to-neighbor economy. If you’re tired of Xcel’s electricity cartel, maybe it’s time to contact your state lawmakers to see if any of them are willing to support legislation that will liberate you, your neighbor, and your community by freeing individuals to own, operate, and enter into private microgrid contracts.

Brit Naas is an energy researcher at the Independence Institute, a free market think tank in Denver.