California’s statute to confiscate all magazines over 10 rounds has been permanently enjoined by the United States District Court for the Southern District of California. The opinion was written by Judge Roger T. Benitez.

Previously, Judge Benitez had issued a preliminary injunction against the confiscation law, and the preliminary injunction was upheld by the Ninth Circuit, as discussed in this post. The March 29 decision follows cross-motions for summary judgment, and makes the injunction permanent. The next step in Duncan v. Becerra will be an appeal to the Ninth Circuit by California Attorney General Xavier Becerra.

The 86-page opinion is the most thorough judicial analysis thus far of the magazine ban question. The opinion is founded on a careful analysis of the record, and thus provides an excellent basis for future appellate review on the merits, perhaps one day by the U.S. Supreme Court.

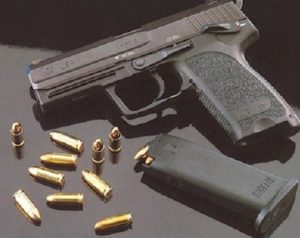

Covering all bases, the opinion analyzes the confiscation law under a variety of standards of review. First is the standard favored by Judge Benitez, what he calls “The Supreme Court’s Simple Heller Test.” In short, magazines over 10 rounds are plainly “in common use” “for lawful purposes like self-defense.” Ergo, they may not be confiscated. The analysis is similar to then-Judge Kavanaugh’s dissenting opinion in the 2011 Heller II case in the D.C. Circuit.

The Duncan opinion then examines the confiscation statute under various levels of “heightened scrutiny”: categorical invalidation, strict scrutiny, and intermediate scrutiny. The confiscation statute is found unconstitutional under each of these standards.

Under the various heightened scrutiny tests, the government bears the burden of proof. The opinion explains in depth why the evidence put forward by the California Attorney General does not come close to carrying that burden. The core problem is that the Attorney General’s evidence, which relies heavily on expert declarations, is speculative, shoddy, or unrelated to the statute at issue.

Nor are there any “longstanding” laws that create a tradition of banning magazines over ten rounds–notwithstanding the Attorney General’s efforts to invent such a tradition based on state machine gun controls enacted in the 1920s or 1930s.

The Attorney General’s argument that law-abiding citizens do not “need” magazines over 10 rounds is rejected as directly contrary to Heller, which defers to the choices of the American people, not the government, about what is appropriate for self-defense. Several incidents detailed at the beginning of the opinion describe the harms suffered by crime victims who had insufficient defensive ammunition capacity.

Moreover, defense against ordinary criminals may be a leading purpose of the Second Amendment, but it is not the only purpose. “Today, self-protection is most important. In the future, the common defense may once again be most important. Constitutional rights stand through time holding fast through the ebb and flow of current controversy.” The government may not respond to bad political ideas by censoring speech, nor respond to crime waves “with warrantless searches and unreasonable seizures. Neither can the g![]() overnment response to a few mad men with guns and ammunition be a law that turns millions of responsible, law-abiding people trying to protect themselves into criminals.”

overnment response to a few mad men with guns and ammunition be a law that turns millions of responsible, law-abiding people trying to protect themselves into criminals.”

Under heightened scrutiny, laws restricting constitutional rights must be “tailored”–in strict scrutiny, “narrow tailoring”; in intermediate scrutiny, “a reasonable fit.” But the confiscation statute “is not tailored at all. It fits like a burlap bag. It is a single-dimensional, prophylactic, blanket thrown across the population of the state.”

The confiscation statute cannot be saved by invoking the mantra of “deference.” First of all, the confiscation law was enacted by ballot initiative, and not by the California general assembly. No deference is due to ballot measures that infringe constitutional rights. Even if the statute were a legislative enactment, the statute is not proven to be constitutional simply because the government offers some evidence. Some courts in Second Amendment cases have adopted an ultradeferential “some evidence” standard, but Judge Benitez disagrees. As he points out, the key case cited by advocates for ultradeference is the Supreme Court’s Turner II decision, upholding certain congressional mandates on cable television providers. The Supreme Court majority in Heller rejected Justice Breyer’s dissent urging Turner deference in Second Amendment cases. And even if Turner were the controlling case, the Turner Court was hardly lax in its judicial review. The Supreme Court “extensively analyzed over the course of twenty pages the empirical evidence cited by the government, and only then concluded that the government’s policy was grounded on reasonable factual findings supported by evidence that is substantial for a legislative determination….Turner deference does not mean a federal court is relegated to rubber-stamping a broad-based arbitrary incursion on a constitutional right founded on speculative line-drawing and without any sign of tailoring for fit.”

Congratulations to plaintiffs’ attorneys Michel & Associates. While a three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit lies ahead, and so perhaps do an en banc and the Supreme Court, today’s opinion is a victory for serious judicial review of arms confiscation laws.

Dave Kopel is research director at the Independence Institute, a free market think tank in Denver. A version of this originally appeared in The Volokh Conspiracy legal blog.