GREELEY —Where former Democrat State Rep. Rochelle Galindo actually spent $4,500 of her campaign cash, and whether or not it was for defending criminal charges unrelated to her campaign, may never be known because of rules written by the Secretary of State and placed into law by the Democrat majority in the last session — including Galindo.

Galindo stepped down from her office representing House District 50 in Greeley on Mother’s Day amid accusations she sexually assaulted two staffers during her campaign for office. She was in the midst of a recall and said at the time the allegations against her were false but would be hard to surmount in a recall battle.

Ten days after she stepped down, she received a summons for “unlawful acts.” She has appeared in court on that complaint, and now has a pre-trial hearing scheduled for Dec. 20. She is charged with providing alcohol to a minor, a Class 1 misdemeanor, which carries possible penalties of up to 18 months in jail and fines up to $5,000 or both.

However, she didn’t close out her campaign finance account with the Secretary of State’s office until just recently, and in her final filling, she reimbursed herself $4,500 for what she reported as legal fees related to her recall.

However, what legal costs may have accrued at the time she stepped down is unclear as signatures were still being gathered against her, so such actions as challenges to signature validity had not occurred yet.

Additionally, a filing by the recall committee asking the court for a finding on whether out-of-state residents could be used to gather signatures went unchallenged by Galindo, said Stacey Kjeldgaard, spokeswoman for the group who organized the recall campaign.

Galindo’s campaign has not returned multiple requests for comment from Complete Colorado.

Under Colorado campaign finance laws candidates cannot use their funds for “personal purposes not reasonably related to the election of the candidate except that a candidate committee may make expenditures to reimburse the candidate for reasonable and necessary child or dependent care expenses the candidate incurs in connection with their campaign during the election cycle.”

Although recall expenses could be considered an allowed expense, Matt Arnold, director of Campaign Integrity Watchdog sees problems with Galindo’s filing

According to Arnold, who follows campaign finance laws closely, in order for Galindo to “reimburse” herself, first, she had to have reported a loan or in-kind donation of some sort for the same amount, and she also was required to report who was actually paid the money and when. And all the amounts needed to match up.

According to Arnold, who follows campaign finance laws closely, in order for Galindo to “reimburse” herself, first, she had to have reported a loan or in-kind donation of some sort for the same amount, and she also was required to report who was actually paid the money and when. And all the amounts needed to match up.

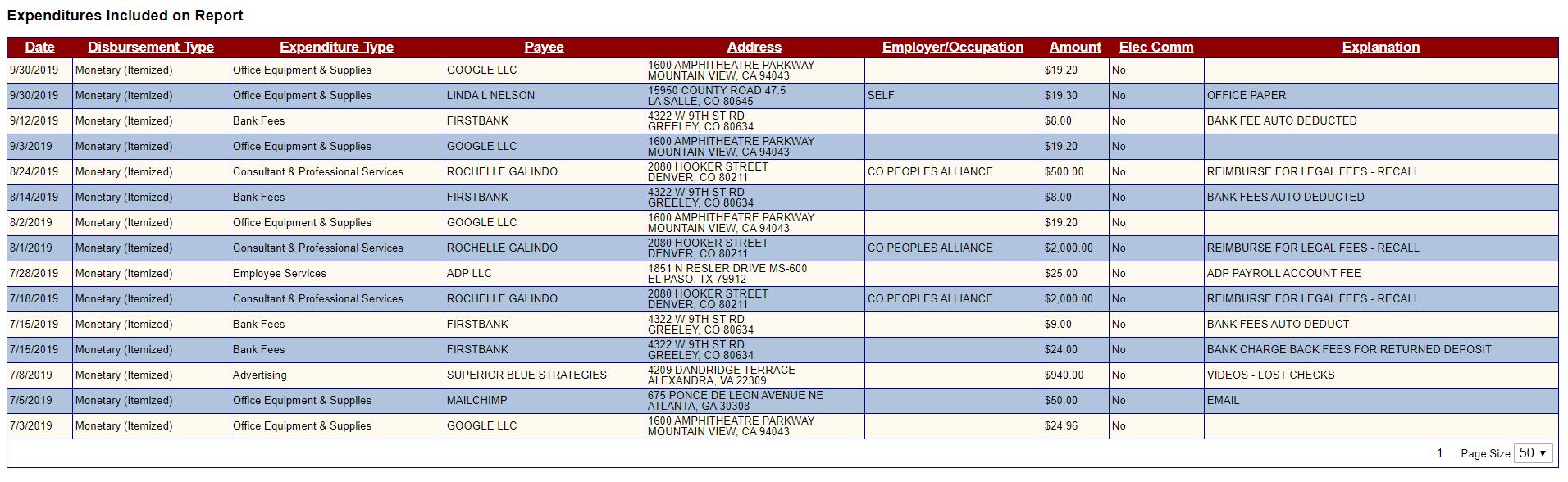

Complete Colorado looked over all her filings dating back to a pre-recall timeline, and Galindo did neither. All Galindo reported was three separate “reimbursements” to herself to tallying the $4,500.

Yet, laws supported by the Secretary of State’s office and put into statute in the last legislative session are seemingly void of any transparency for Galindo’s donors, despite Jena Griswold running her campaign on a platform of transparency.

Griswold did not comment on the subject. However, according to Serena Woods, Communication’s Director under Griswold, receipts by a candidate are not open for inspection under Colorado Open Records laws; the only way Griswold’s office would look into the report is if someone filed a complaint against her for that reason; and even if Griswold’s office investigated, any receipts presented under discovery would be considered “work product” and still would not be open to public inspection.

Essentially, there is not much oversight or accountability to political candidates and how they spend the money, Arnold said.

Arnold said the likelihood of Griswold sending a complaint to a judge for prosecution is slim to none, noting that since June of 2018, when new laws were first being discussed under then-Secretary of State Wayne Williams, 63 campaign finance complaints have been filed, but only two have reached any kind of settlement and one is still pending.

“Everything is handled by the administration. Everything is under wraps,” said Arnold. “There is no transparency or accountability. Their rules are contrary to the constitution. Article 28 (of the Colorado Constitution) calls for strong enforcement of campaign finance laws and full and timely disclosure The Secretary of State continually violates that constitutional mandate.”

Arnold said Galindo’s filing is prime for a complaint, but anyone filing should be prepared to follow it through the process, noting that Griswold rewrote and overhauled many of the rules put in place by Williams when she took over the office in January 2019.

“Be ready and willing to fight the Secretary of State at every turn and every step of the process to make sure the law is followed,” Arnold said.