Mayor Michael Hancock of Denver and Governor Jared Polis of Colorado have each instituted stay-at-home orders covering their respective jurisdictions.

Both orders have generated both confusion and push-back. In addition to the general concern about long-term economic damage to the state and the city, many citizens feel cramped by the abridgement of rights and privileges they never conceived could be curtailed.

The restrictions here in Colorado and Denver would have been a lot less controversial if they had been better thought-out and less arbitrary.

Between what constitutes an “essential business,” what activities are permitted, and how much travel is permitted, and what jobs are “essential,” nobody walked away from those press conferences confident that they knew what the rules meant.

Maybe not even the people writing them.

Nevertheless, the average citizen is expected to abide by them. What’s more, the orders are written in such a way to that the that the real power lies with regulatory agencies like the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDHPE), who can redefine them as desired.

In the mayor’s press conference, one reporter asked whether liquor stores were considered essential. “They are to me,” replied Mayor Hancock, chuckling. Except he was replying to reporters, who have a reputation for drinking their breakfasts. By the time the fourth question about liquor stores and pot shops had been asked and sort of answered, the line into Denver’s Argonaut Liquor stretched for two blocks, even without social distancing.

Eventually, they mayor figured out that pot, liquor, and guitar stores were essential businesses, as long as they practiced social distancing, but dry cleaners, book stores, and thrift shops weren’t. The basis on which he made these designations remains murky at best, except perhaps for the liquor stores.

Then, sometimes, it appears that neither the elected officials nor the regulatory authorities know what their constraints are. Initially, the mayor claimed that Denver residents traveling to their “non-essential” jobs in other counties would be stopped and turned around, violating a well-established constitutional right to travel. Similarly, it took Gov. Polis two press conferences to admit that right, and that it extended to anywhere within the state as well as to other states. No matter what the San Juan sheriff’s office says.

And eventually, when they do know what the constraints are, but they want people to abide by rules that might be outside their power to enforce, both officials dodged questions about enforcement, imploring citizens to “do the right thing,” but perhaps under duress.

![]() It also doesn’t help that in some cases, elected officials appeared to have offloaded their decision-making responsibility to technocrats. There’s nothing wrong with the Tri-County Health Department making recommendations, but they can’t be removed from office by irate citizens. Ultimately, those decisions need to be made by county and city councils and executives.

It also doesn’t help that in some cases, elected officials appeared to have offloaded their decision-making responsibility to technocrats. There’s nothing wrong with the Tri-County Health Department making recommendations, but they can’t be removed from office by irate citizens. Ultimately, those decisions need to be made by county and city councils and executives.

Press conferences can be awfully ugly sausage-making, and reporters will ask the same questions in multiple ways to try to get clarity. But the idea that Hancock didn’t have quick, easy answers about walking your dog in city parks, or that Polis didn’t know that he can’t stop you from going up to the backcountry to snowshoe, is absurd. They had to know those questions were coming, and they still ended up dancing around them.

In the meantime, it’s hard to escape the notion that government is taking care of itself. The state government is expected to be down $500 million in revenue this fiscal year and Denver is looking at a $40 million shortfall. But at no press conference has any reporter asked if non-essential government employees will be required to take vacation while they’re at home, or if furloughs are being considered. At some point, citizens are going to be asking themselves just who’s supposed to be working for whom.

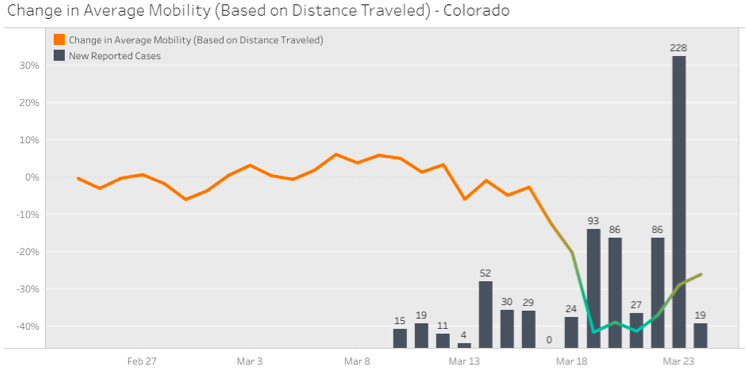

In fact, there’s some evidence that frustration is already starting to build. Unacast has begun tracking decreases in social mobility using aggregated and anonymous cell phone activity and location data. Colorado’s “score” peaked on March 19 at an A grade and a 42% decline in social mobility. But from March 21-March 24, mobility increased and the score dropped to a C, perhaps helping to precipitate the governor’s order:

In more recent days, the score has returned to -42%; it remains to be see how long it stays there.

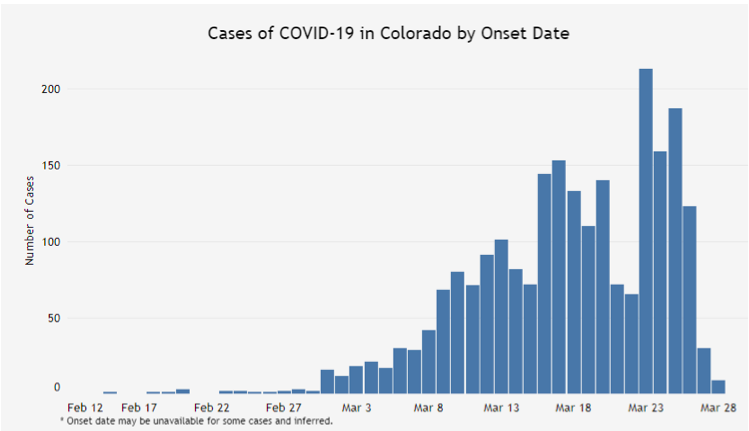

These greater restrictions are being placed even as the rate of new cases appears to be declining:

Naturally, we should be careful here. There’s a lag between when someone contracts the virus and when they’re diagnosed. If someone had looked at this chart on March 22, they would also have concluded that the new case load was declining, only to be surprised by a spike the next day.

Americans in general and Coloradans in particular are a generous crowd. We want to help each other, and are willing to sacrifice in order to do so. But we also like to know what the rules of the game are, and that we’re not being pushed around by elected officials and risk-averse bureaucrats who never lost a job for saying, “No, we need more time.”

Governor Polis and Mayor Hancock would stand a much better chance of getting and keeping the public behind them if they thought through their orders and stuck by them, rather than making dramatic, but plastic announcements.

Joshua Sharf is a senior fellow in fiscal policy at the Independence Institute in Denver.