A recent report from Channel 4’s Brian Maass that Denver has overpaid about $11 million in pension benefits over a period of 15 years brings up serious questions about the overall financial state of Denver’s public pensions.

The short answer: they’re better off than the state’s Public Employees Retirement Association (PERA), but still have serious problems of their own.

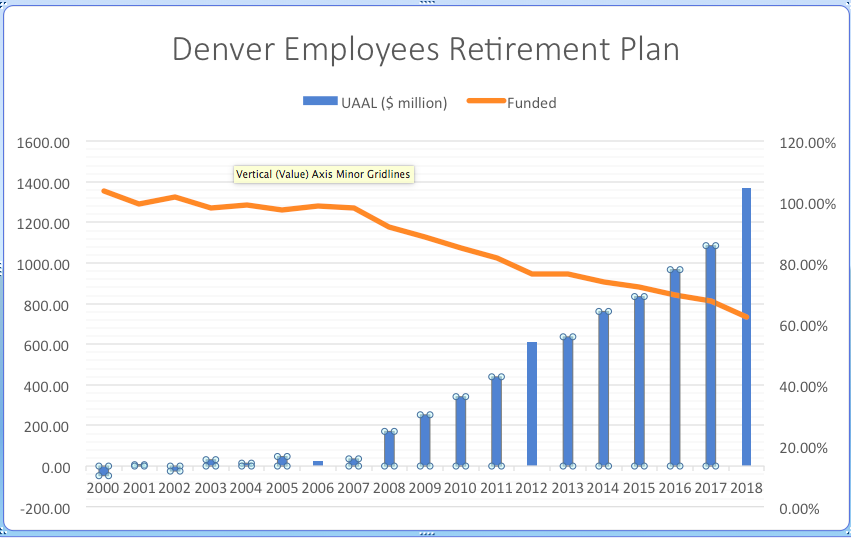

The Denver Employees Retirement Plan (DERP) is currently funded at about 62%, meaning that it has about 62 cents on hand for every dollar’s worth of promises that have been made. This may come as a surprise to many readers, since unlike PERA, Denver’s pensions were well-funded – at over 90% – until the 2008 financial crisis.

Also unlike PERA, Denver has consistently made its Actuarially Required Contribution (ARC), and has consistently increased both employer and employee contributions. And in 2016, in order to encourage fiscal responsibility, DERP switched from an open-ended 30-year amortization to a closed 30-year amortization, with about 27 years remaining as of the end 2018. Note that the ARC is not a legal requirement, but an accounting one; it is the amount required to keep the plan on track for its amortization goals.

Why, then, has the plan’s funding declined over the last decade?

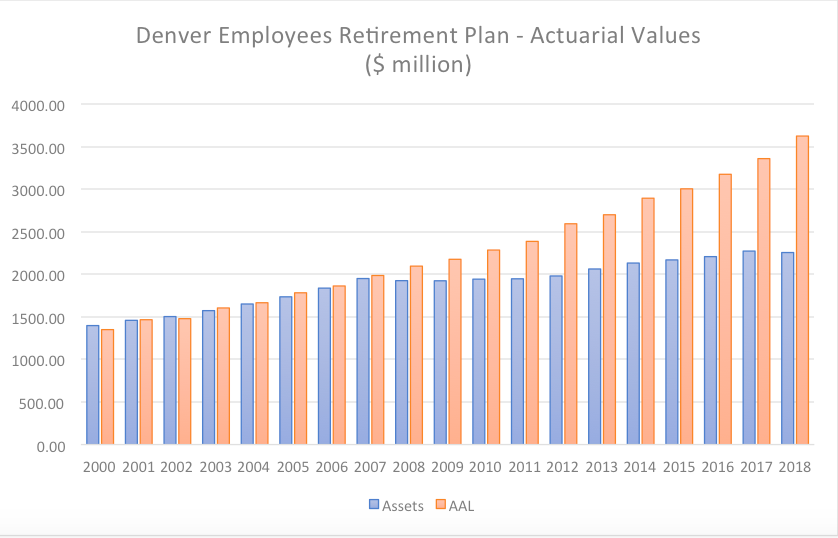

Up until the 2008 financial crisis, the plan was at or nearly at 100% funding. It continued to stay there, either slightly over-funded or with miniscule unfunded liabilities through 2007. Then, even as the liabilities continued to rise, actuarial assets stagnated, essentially not moving at all between 2007 and 2012:

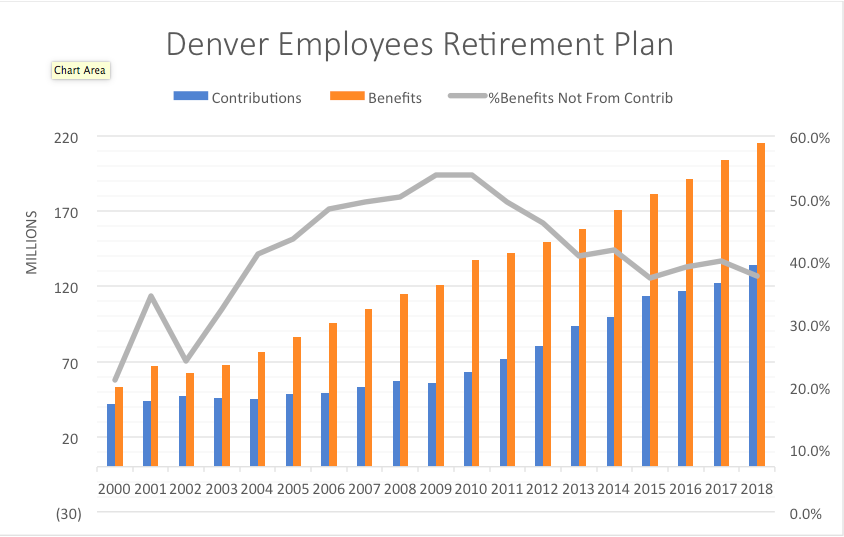

Realizing the problem, Denver began to ramp up both its employer and employee contributions beginning in 2010. Over the next eight years, employer contributions gradually increased from 8% of salary to 12.5%, while employee contributions grew from 2% to 8%.

This got contributions out of a rut they had been stuck in from about 2000, but benefits paid out continued to climb, as well:

The gray line represents the percentage of benefits paid out that were not covered by that year’s contributions, i.e., the percentage of benefits that had to be covered out of investment returns or out of assets. Annual contributions had barely budged, but benefits continued to grow both from inflation and from an increase in the number of retirees. From 2000 to 2007, the total contributions increased at a 3.4% annual rate, while the dollars paid out in benefits grew at 10.3% per year.

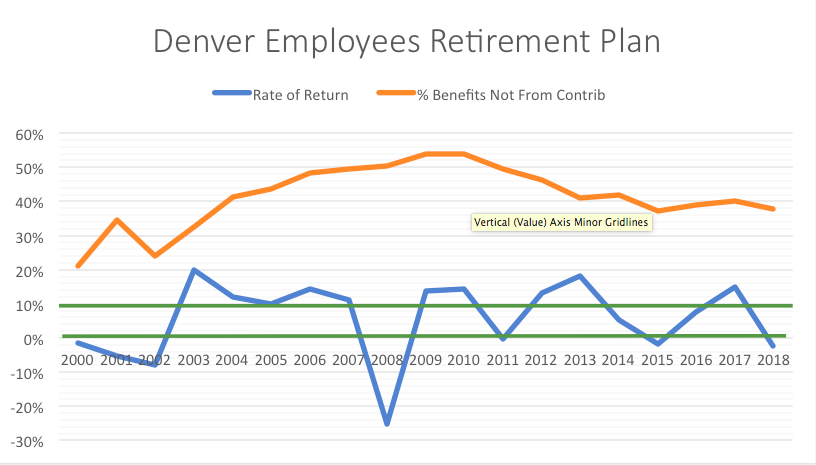

This was fine as long as returns were good, masking the need for increased contributions. From 2003 – 2007, returns were well above the expected 8%, allowing the plan both to cover the increase of benefits relative to contributions and build plan assets.

But this was illusory. Such returns couldn’t continue indefinitely, and the 8% discount rate helped make the plan liabilities look smaller than they should have, had a more realistic discount rate been used. Also, actuarial smoothing probably helped make things look better than they would have, had the market value of assets been reported instead.

(The year 2002 was something of an outlier – contributions increased, benefits paid out decreased, and so the plan funding actually increased, despite a -7.8% return on assets, the worst of the three negative returns from 2000-2002.)

Such returns couldn’t continue–and indeed they didn’t–with Denver suffering along with everyone else in 2018, and seeing a negative 25% that year.

Even though the plan’s average return from 2009-18 has been almost exactly 8%, returns have been volatile, and as we know from other plans, bad years hurt more than good years help, and that’s been the story with the Denver plan, as well. In 2013, for instance, investments returned over 18%, but the funded ratio barely budged. In 2015, after most of the contribution increases had kicked in, the plan returned 15%, and the funding ratio still declined by 2%.

As of 2018, the unfunded liability was at nearly $1.4 billion, close to the total Denver operating budget. When the 2019 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) is released in a few weeks, we shouldn’t expect that amount to have declined much, if at all. So far, 2020 isn’t looking so good, either.

At a time when Denver’s new progressive City Council has decided to spend tens of millions of dollars on green dreams and social justice, perhaps it’s time to pay attention to the nuts and bolts of city finance instead.

Joshua Sharf is a senior fellow in fiscal policy at the Independence Institute, a free market think tank in Denver.