DENVER–As the Colorado Division of Parks and Wildlife (CPW) grapples with the process of forcibly introducing gray wolves into western Colorado–as dictated by last year’s Proposition 114–the predicted costs of importing and managing wolves continues to rise.

In the fiscal note for the initiative, the Legislative Council Staff (LCS) predicted a two-year cost of $811,710 just to get the forced wolf program up and running, and could not predict costs beyond 2023.

Proposition 114 passed with a narrow margin of just over 56,000 votes statewide, with the outcome heavily influenced by Front Range metropolitan voters. Overall, roughly 62% of Western Slope voters, who will live with the actual consequences of wolf importation, said no to the measure, but it wasn’t enough to overcome the Front Range voter advantage.

Only one of five bills in the state legislature this session directed at wolf program funding and management still survives, so far. House Bill 21-1243 would amend the statute by easing the financial burden on the wildlife cash fund, which is primarily funded through hunting and fishing license fees.

The bill’s fiscal note says it “assumes that under current law, the Wildlife Cash Fund is the default fund source to be used.”

The LCS estimates that the ongoing annual cost of the program will be “approximately $800,000 per year.”

In the draft state budget for FY 2021, which begins in July, $5 million was scheduled to be appropriated for the program, but in the last round of budget negotiations that amount was reduced to $1.1 million, which is far higher than the $311,768 the LCS says is required for FY 2021-22.

Big game depredation has serious economic consequences

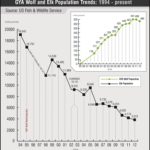

According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, after the 1994 forced wolf introduction to Yellowstone National Park, through 2012, elk herds decreased by more than 80%. Most of the natural dispersion of wolves in the west since 1994 centers on the Yellowstone packs. As wolf populations increase and prey species decrease wolves migrate in search of better prey opportunities and open range for the new packs.

In Wyoming, the decimation of the elk herds is obvious to “anyone in consumptive wildlife usage in Wyoming,” said former Colorado wildlife commissioner Rick Enstrom, “We’re going to be spending a lot money on this before it’s over.”

Reduced big game herds means fewer hunting opportunities and a diminished hunting experience, especially for out-of-state hunters who spend far more on licenses than residents. A resident bull elk license is $56.88. A non-resident license is $688.26.

Diminished hunt satisfaction also translates directly into lower tax revenues for counties and communities that depend heavily on annual hunting revenues.

And then there’s the moose.

In Wisconsin, Minnesota and Alaska moose calves are a favorite food source for wolves, particularly in winter, and moose populations have suffered under wolf-protection laws.

“There have been public statements by the proponents that they are hoping to have 500 wolves in Colorado at some point,” Ted Harvey, a political consultant and former state Senator who ran the Stop the Wolf PAC in the run up to the 2020 election told Complete Colorado. “That is just the epitome of foolishness when you see what the devastation is to the herds in the northern Rocky Mountains or in Minnesota and Wisconsin. We have spent a ton of money on the introduction of the moose into Colorado over the last 40 years. Now we’re just going to say, too bad we’re going to introduce wolves?”

Wolves are abundant and Idaho is sick of them

According to the first of three “educational sessions” presented by CPW to the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commission (CPWC) and some 400 interested persons in an April 28 Zoom meeting, Dr. Diane Boyd, wolf expert and an affiliate faculty member at the University of Montana said Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Washington, and Oregon spend between one and two million dollars each year on wolf management.

Boyd said in 2020 Wyoming had 311 wolves in 43 packs, Idaho had 1,556 wolves in 80 to 100 packs, Montana had 1,136 wolves in 190 packs and Oregon had 173 wolves in 22 packs.

Elk in the north-central Lolo zone of Idaho, south and east of Coeur-d’-Alene saw a steady decline from about 8,000 in 1999, when wolves became established there to about 2,500 in 2011, according to a slide presented at the educational session by Jon Horne, Senior Wildlife Research Biologist for Idaho Fish & Game.

The wolf depredation situation in Idaho appears to be so bad that the state legislature just passed Senate Bill 1211 in an effort to mitigate the problem.

Pro-wolf activists claim it would result in the killing of 90% of Idaho’s wolf population, but the bill actually only authorizes control of livestock depredation without a permit and allows an individual to buy an unlimited number of wolf tags “when seasons are open at the time of the take.”

Wolves as a ‘bottomless pit’ of spending

“We could use the entire CPW budget for managing wolves and that probably still wouldn’t be enough, whether it’s [wolf predation] compensation or management, because it’s kind of a bottomless pit,” state Representative Matt Soper, R-Delta, told Complete Colorado. “If we start taking money from [CPW habitat] projects and putting it towards wolves, what happens to all those other areas we’ve been working so hard to develop?”

Soper says it is unfair for hunters and fishermen to pay for a license to go out and harvest wild game and then have that money used to fund wolf introduction that will damage Colorado’s valuable big game hunting opportunities.

“You have an apex predator that would be taking those fees, which is actually diminishing the quality of the hunt and the availability of game for you to harvest,” Soper said. “It’s a circular self-destruction formula we’ve created.”

‘Reeducation’ campaign by CPW underway

On April 22, CPW announced that it had “selected the Keystone Policy Center, headquartered in Keystone, CO, as the facilitation partner to help guide the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commission in the upcoming public involvement process for gray wolf reintroduction efforts in the state.”

The CPW is a division of the Colorado Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and Dan Gibbs, DNR Executive Director, is the husband of Johanna Raquet Gibbs, a Senior Policy Director at the Keystone Policy Center.

“Parks and Wildlife is a great agency and has a great PR team already,” said Soper. “They don’t need to have an outside PR firm to tell us how wonderful wolves are, because the reality is they are being introduced. An overwhelming number of counties voted against wolf reintroduction in Colorado. This is really just to ‘reeducate’ western Colorado into a certain way of thinking.”

Neither the DNR nor the CPW responded to a request for the amount Keystone is going to be paid for its services before press time.

Pingback: Cost of Colorado’s forced wolf introduction already rising; a ‘circular self-destruction formula’ - American Colors