Just when you thought it couldn’t get any worse for drivers, the Denver Regional Council of Governments (DRCOG), has joined the war on cars.

DRCOG is a planning organization made up of dozens of metro Denver counties and municipalities.

Several weeks ago, the Council voted to steal $210 million from roads and highways for “mobility,” and to demote relieving traffic congestion on its list of priorities. In theory, this is being done to bring DRCOG into line with the Colorado Department of Transportation’s (CDOT) revised priorities.

According to DRCOG: “Projects include 60 miles of bicycle and pedestrian facilities, enhancing connections to transit; street improvements for pedestrians, cyclists, transit riders and other multimodal travelers; updates to intersections for vehicle and transit services operation; and safety projects to help prevent accidents.” Council President Kevin Flynn, who is also a Denver City Councilman, argues that the change represents the “new reality” that mobility must focus “on allowing people to move around without automobiles.”

One thing you can be certain of: an increased focus on mobility as Flynn and DRCOG define it will leave the region’s drivers increasingly immobile.

Transit in decline

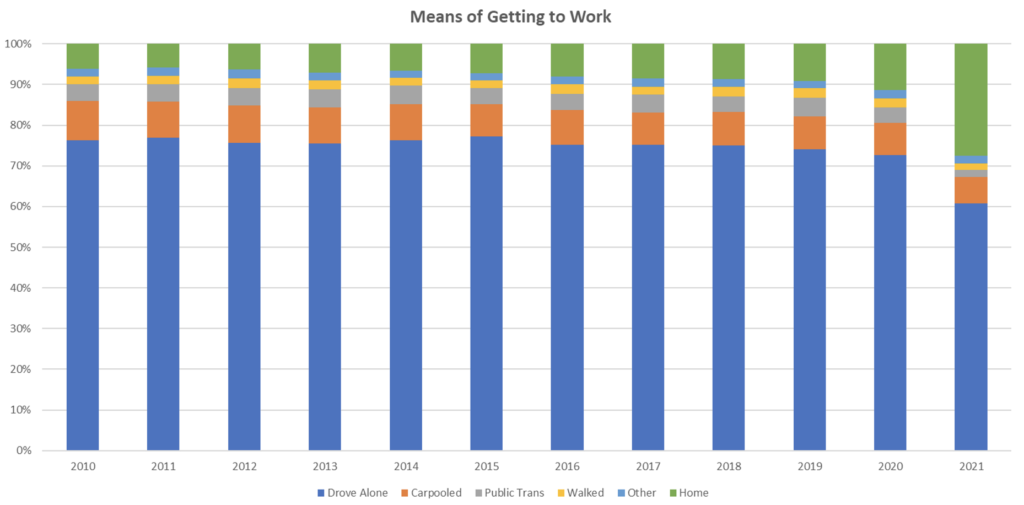

From 2010 to 2019, according to US Census statistics, the number of commuters in the Denver area grew from 1.26 million to 1.62 million, an increase of 365,000 or nearly 30%. During that time, despite increased spending on light rail, bike sharing, bike lanes, scooters, and improvements for pedestrians, the percentage of commuters using public transportation barely budged, from 4.1% to 4.5%, and those commuting by “taxicab, motorcycle, bicycle, or other means” dropped from 1.9% to 1.8%.

But it was during the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions that transit’s fragility became apparent. In 2021, the share of those working from home climbed to 27.5%; the number of commuters driving either alone or in car pools dropped from 80% to 67% because of the sheer volume of drivers. The number of those using public transportation cratered to 1.7%, slightly over 1/3 of what it had been two years before.

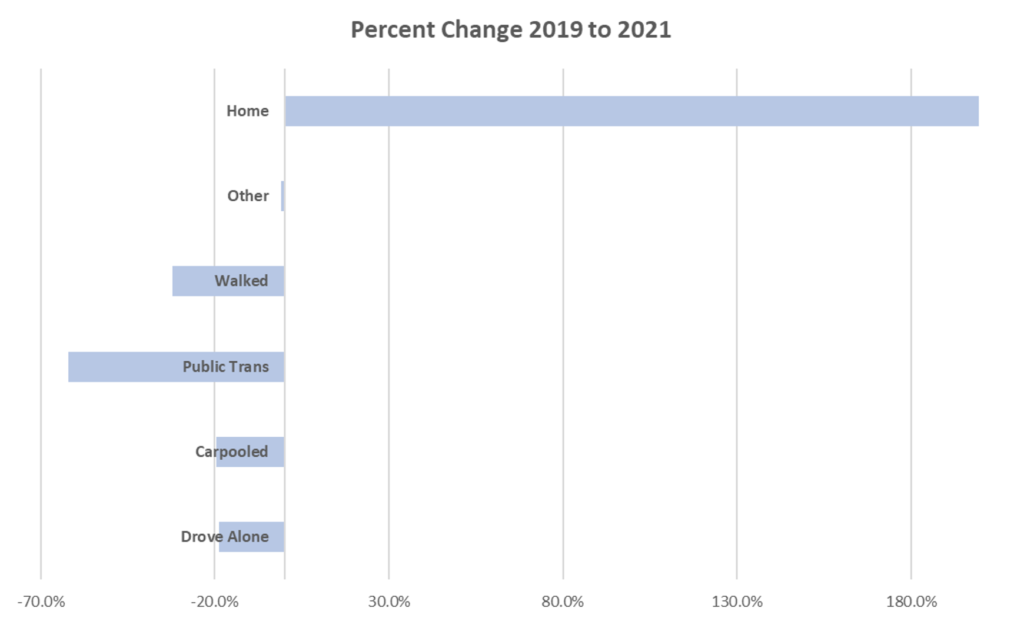

Because public transportation was never more than 4.5% of the total, it’s actually hard discern the true scope of its collapse in the graph. Below is the percentage changes for each mode of transport from 2019 to 2021. Public transportation usage dropped by 5/8 as working from home tripled. Driving was down a mere 20% by comparison. These numbers are even worse than the national totals, where public transit usage dropped by 50%.

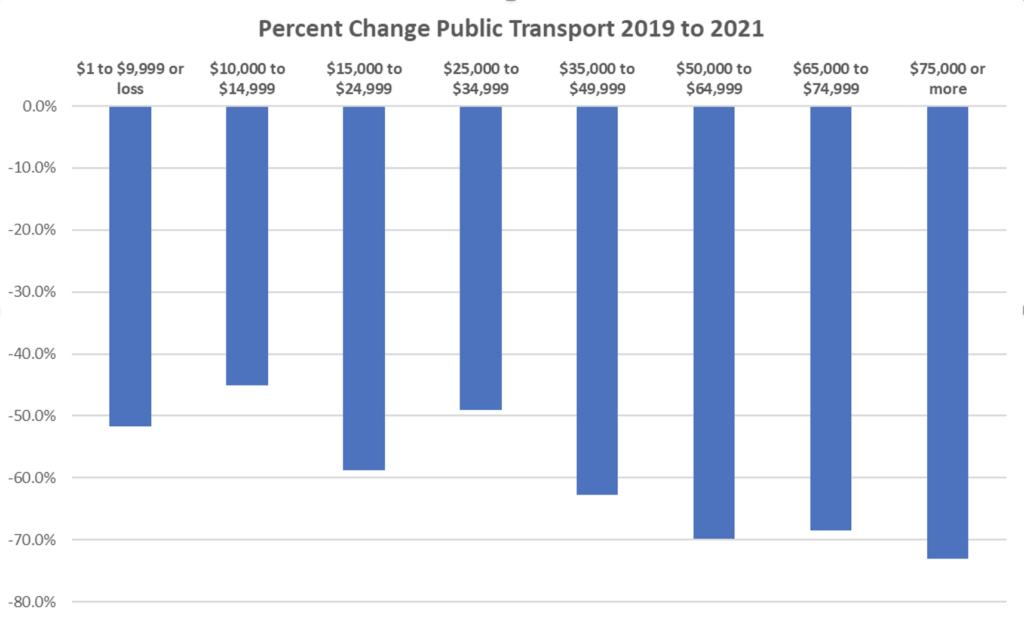

More than that, the very upper-income people who the light rail had been built for were the fastest to abandon it. From 2010 to 2019, the percentage of riders making more than $50,000 had risen from 30% to 43%, and the percentage making more than $75,000 had risen from 16.7% to over 23%, largely as a result of added light rail routes. But they were the riders quickest to go to work from home. This outcome is even more ironic given that these routes are heavily subsidized through low-income Coloradans through regressive sales taxes.

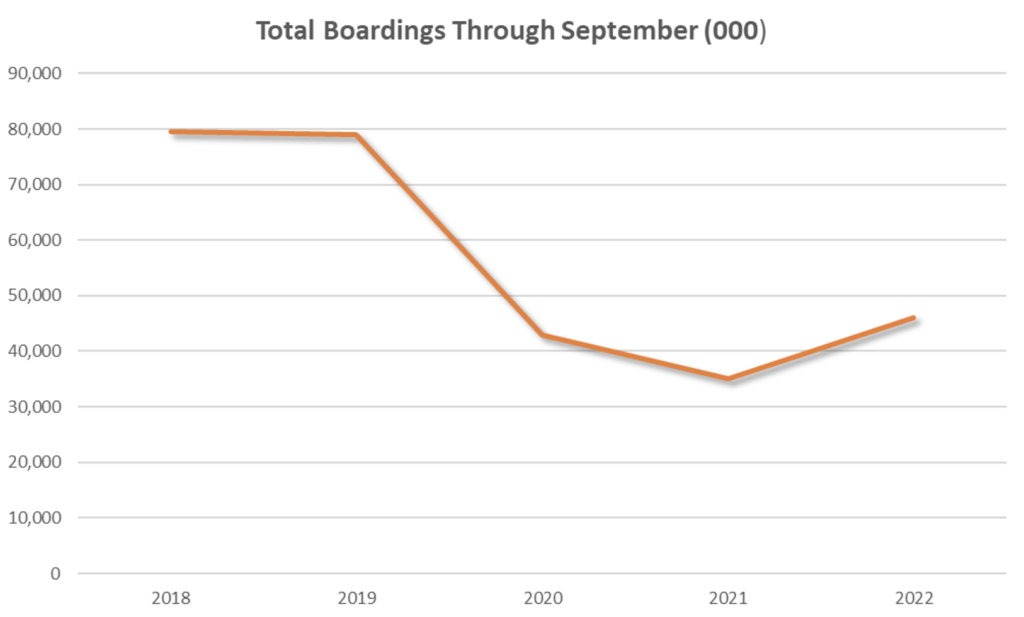

RTD’s ridership numbers have not even come close to recovering.

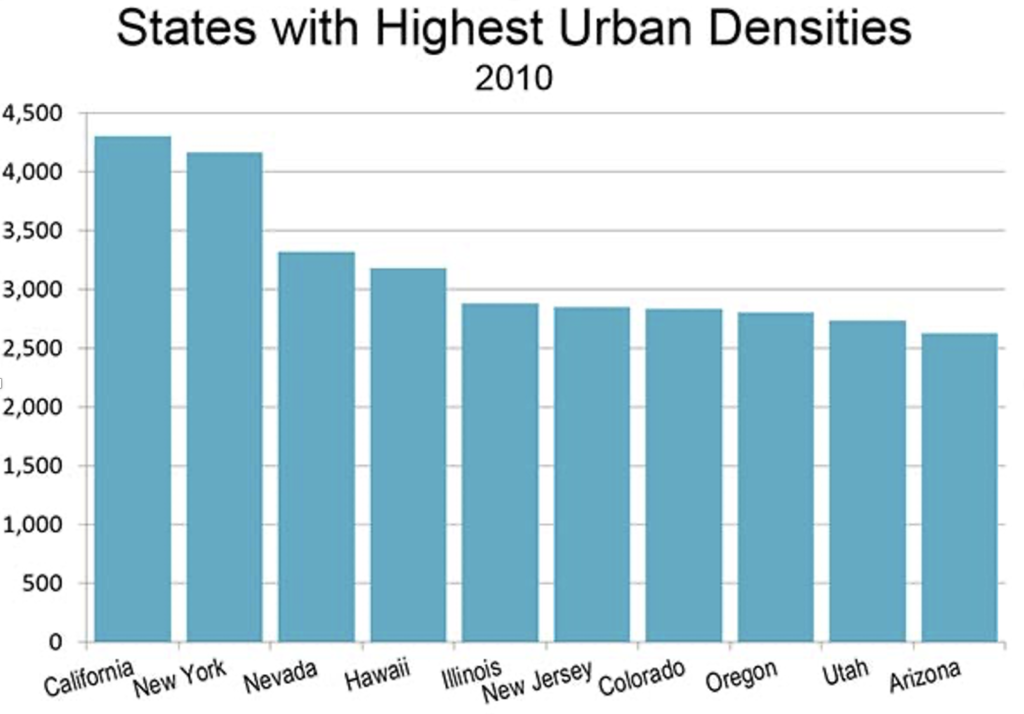

On his way out the door, Governor Hickenlooper tied the state’s Air Quality Control Board’s policies to those of California. As Wendell Cox points out, density makes traffic worse, not better, since everyone is trying to use the same roads at the same time. Even before California adopted Senate Bill 375 with its radical densification, it had the highest urban density in the country. (Urban density is a measure of how densely packed a state’s urban areas are, not a measure of how many of its people live in urban areas.) What may be surprising to some is that Colorado already has the 7th-highest urban density in the country, on a par with New Jersey and Illinois, and not that far behind Hawaii and Nevada.

Cars are the answer, not the problem

What’s worse, up until now DRCOG had been a relatively weak and toothless organization. Member municipalities were free to comply with or ignore the Council’s guidelines. With recent legislation, it will have the potential to impose fees and taxes on its own (although new taxes will still require a vote of the people affected), giving it an independent revenue stream and the power to reward or punish compliance.

With DRCOG’s action, the doors of one of the last levels of government not ideologically committed to making life difficult for drivers slammed has shut on them. The federal government has said it will give priority to infrastructure projects that promote transit. CDOT moved to de-prioritize roads late last year partially in response to the state legislature’s Senate Bill 21-260. Denver has been removing traffic lanes from major surface streets for bikes and bus rapid transit, and has made it clear that drivers are not a priority. And Governor Polis failed to ask for a waiver to federal air quality rules, which will likely lead to about a 50-cent per gallon price hike starting early next year.

All this, despite the fact that most commuters would apparently rather live in their cars than give them up. Even with increasing congestion, the number of drivers continues to climb. People simply love and need the flexibility and independence that the automobile gives them, despite the inconvenience it presents to urban planners.

If the problem were the accessibility of public transportation, RTD could shift its focus from trains to buses, and increase bus service to underserved areas. Denver and other local governments could make a point of purchasing bus cut-outs, especially along important surface streets, to speed traffic flow around stopped buses.

Instead, the civic planners from Washington on down seem intent on telling people how they ought to live, rather than making it easier for them to live the way they clearly want to.

Joshua Sharf is a senior fellow in fiscal policy at the Independence Institute, a free market think tank in Denver.