Colorado Senate Bill 213 will make housing less affordable and increase greenhouse gas emissions. This is exactly the opposite of what its proponents claim.

Surveys show that 80 percent of Americans want to live in single-family homes. Recent census data reveal that more than 80 percent of the residents of 14 states do live in single-family homes.

Colorado isn’t one of them.

Census data also show that more than 80 percent of the residents of more than 30 percent of the nation’s urban areas live in single-family homes.

The Denver urban area isn’t one of them.

Neither are the Boulder, Ft. Collins, or Longmont urban areas. However, more than 80 percent of the residents of both the Colorado Springs and Pueblo urban areas do live in single-family homes. In Pueblo it’s almost 85 percent.

Boulder and Denver fall short not because more people want to live in apartments than in other parts of the country. Instead, it is because planners have deliberately made single-family housing expensive by making new development difficult in the areas outside of city limits.

Boulder has a huge greenbelt that has helped make it the least affordable urban area in the nation outside of California or Hawaii. Denver has an urban-growth boundary that has nearly doubled the cost of single-family homes. Meanwhile, El Paso and Pueblo counties have some of the least-restrictive zoning in the state, enabling more residents of Colorado Springs and Pueblo to achieve their dreams of single-family homeownership.

Dense doesn’t mean affordable

The backers of SB-213 claim it will make housing more affordable. In fact, it will make it less affordable.

The bill as amended in the House of Representatives requires many cities to amend zoning ordinances to allow developers to tear down single-family homes and replace then with dense housing developments near high-frequency bus lines and light-rail stations (a statewide mandate for such upzoning was stripped out of the bill in the Senate).

In other words, the bill will reduce the supply of the kind of housing that at least 80 percent of Coloradans want to live in. This will drive up the price of the remaining single-family homes in those areas, making housing less affordable, not more affordable.

Imagine that there was a shortage of pickup trucks. Since pickups are used by plumbers, electricians, and other contractors, the shortage was driving up all sorts of costs. One pickup weighs as much as two subcompact cars, so to relieve the shortage, the Colorado legislature proposes a bill to scrap pickups and use the materials to build subcompact cars. Would that relieve the shortage of pickups? Obviously not. Yet some Colorado legislators think that replacing homes that people want with homes that people don’t want will make housing more affordable. It won’t.

SB-213 also requires cities to allow for the construction of more so-called transit-oriented developments. You may have seen these mid-rise (four- to six-story) apartment buildings popping up all over metro Denver and other Colorado cities.

These stack-n-pack developments are hardly affordable. As California developer Nicholas Arenson recently testified to a San Francisco planning commission, the need for more steel, concrete, and elevators makes such housing far more expensive to build, per square foot, than single-family homes. Demand for living in them is low, so most of them are subsidized.

Even with subsidies, these mid-rise apartments are only “affordable” because they are chopped up into small apartments, often 1,000 square feet or less. In some of these buildings, the rent on a 900-square-foot apartment is more than the monthly mortgage payment on a 2,000-square-foot house in Colorado Springs or another city that doesn’t severely restrict rural development.

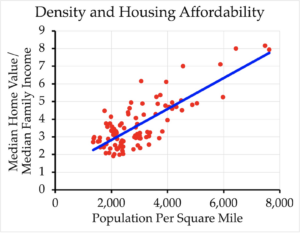

SB-213 is based on a flawed premise: that denser cities are more affordable. In fact, the opposite is true. As shown in the chart comparing housing affordability with density in the nation’s 100 largest urban areas, the nation’s densest urban areas are the least affordable, while the most affordable urban areas have the lowest densities.

As the blue trend line shows, census data reveal that density makes housing less affordable. The 2020 census calculated the population density of the nation’s largest urban areas. The Census Bureau’s 2021 American Community Survey measured 2020 median home values and median family incomes. Housing affordability is commonly measured by dividing median home values by median family incomes; 3 or less is affordable, 4 is marginally affordable, 5 or more is unaffordable. For the nation’s 100 largest urban areas shown in this chart, the correlation between density and unaffordability is 0.8, meaning this is far from random.

Sprawl isn’t a dirty word

Planners also say that urban-growth boundaries and other rural land-use restrictions help protect farms, forests, and open space. But the 2010 census found that all of the urban areas in Colorado covered just 1.5 percent of the state. Data from the 2020 census indicates that it is still just 1.5 percent. So-called sprawl (which is really just people living the American dream of single-family homeownership) is no threat to Colorado’s farms, forests, or open space.

Density doesn’t reduce greenhouse gases

Planners admit that SB-213 will build housing that people don’t want to live in. But they say Colorado needs to force people to live in higher densities in order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. They are wrong about that too.

Data from the Department of Energy suggests that people who live in denser areas tend to drive a little less. But, the data show, they also drive at slower speeds in more congested traffic, which wastes more fuel. As a result, driving in denser urban areas uses more energy and emits more greenhouse gases, per capita, than driving in low-density areas. If Colorado wants to be climate friendly, it needs to allow more people to live in low-density, single-family neighborhoods.

Senate Bill 213 is not about making housing more affordable. Nor is it about reducing greenhouse gas emissions. It is about the government trying to force people into ways they don’t want to live, including forcing more people to rent cramped apartments rather than owning their own single-family homes. The legislature should firmly reject this bill.

If Colorado wants to make housing more affordable, it should eliminate urban-growth boundaries and other restrictions on rural land development. Yes, that might lead urban areas to cover 1.6 or 1.7 percent of the state instead of just 1.5 percent. But isn’t that better than forcing young families to move out of the state because they can’t afford housing in Colorado?

Randal O’Toole is a land-use and transportation policy analyst, the director of the Thoreau Institute, and director of the Independence Institute’s Transportation Policy Center.