Every March, it’s the same story – literally. Local media run a series of lazy stories about the alleged gender pay gap, mixing up aggregate and individual statistics, and mentioning–then discarding–career and life choice differences.

This year, the Colorado Sun’s Tamara Chuang adds a new twist, the pandemic, which they manage to include with a typical lack of curiosity and critical thought. The article is a mass of logical inconsistency, internal contradictions, and what looks for all the world like a failure to read her own work.

First, she uncritically repeats the claim that the 13-cent difference between men’s and women’s earnings constitutes a meaningful “pay gap.” Then, she quotes at length an economist who gives numerous reasons why that gap doesn’t represent a difference in pay for equal work, without ever quantifying the proper corrections. Finally, she blames the pandemic for a large widening of the gap in 2020, but credits a 2020 law for the post-pandemic return to normal.

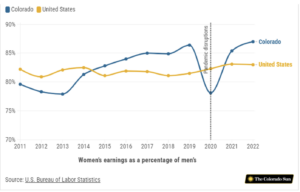

Let’s take these one at a time. Nationally, women early 83 cents for every dollar men do; in Colorado, that number is 87 cents. Typically, this number has been used to claim broad pay discrimination against women, leading to calls for state-level legislation mandating equal pay for equal work.

But analysts and working professionals have been publishing articles for two decades showing that the differences are a result of decisions that women themselves make rather than their employers shorting them. The reasons are remarkably constant over the years – women choose flexibility and lifestyle over pay; women choose lower-paying college majors; women take time off from their careers to raise their children; women work fewer hours than men. Once all those factors are accounted for, the wage gap shrinks to a single penny, which may rankle, but which hardly constitutes a long-term earnings handicap.

Chuang quotes at length Julie Percival, a regional economist for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, who raises all of these points, yet never quantifies the correction that needs to be made. This leaves the impression that much of the 13-cent gap could still be the result of discrimination, when analysis after analysis over the course of decades has shown that it’s not.

In fact, as a higher percentage of college degrees are awarded to women, the raw pay gap, meaningless as it is as a measure of discrimination, continues to close, a fact clearly shown on the Sun’s own graph accompanying its story (see Figure 1).

The drop in women’s earnings compared to men’s during the pandemic restrictions was, and should be treated as, an anomaly. And indeed, last year, that’s exactly how Chuang (who apparently has the Sun’s pay gap beat locked down) treated it:

“The big change over this period was the employment shock that occurred due to the pandemic,” Percival said in an email. And now, “that ratio returns to what we’d expect to see for Colorado — mid-80s.”

But this year, Chuang uses this weird anomaly as the baseline for measuring the effectiveness of Colorado’s equal pay law, which requires greater transparency in wages and salaries. She tracks down an analyst who, through clever use of wage and salary sabermetrics, shows that since Colorado’s “wage gap” improved more from 2020-22 than other states who passed similar laws, that means Colorado’s law must be more effective.

But Colorado’s pandemic drop was among the most dramatic in the country, which you can clearly see from the Sun’s own graph. The analyst compares Colorado’s improvement from 2020 to 2022 to California and Washington State. But California’s “wage gap” went from 11 cents to 13 cents, and Washington’s decreased from 22 cents to 20 cents during 2020. Of course Colorado will show more “improvement,” because, as Chuang reported last year, most of that was just bounce-back from the government’s pandemic restrictions.

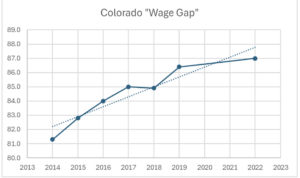

Instead, if you consider 2022 to be the first “normal” year since the pandemic, the improvement to 87 cents is just a continuation of a decade-long trend of improvement, to an R2 of 0.89, or a correlation of 0.94 (see Figure 2). Viewed that way, Colorado’s equal pay law has contributed nothing to a trend that pre-dated it by more than half a decade.

So, as a service to Chuang and her editors, let me list the questions she should have been asking.

- Why did Colorado’s “wage gap” increase so much in 2020 compared to the country as a whole?

- Is it a function of the composition of the labor force, the types of jobs available here, the hours worked, or some combination of the three or some other factor altogether?

- Why has Colorado’s “wage gap” shrunk so much over the last 10 years, along with the country as a whole?

- Once the generally-accepted factors in women’s career and employment decisions are accounted for, how does Colorado’s “wage gap” compare to the 1-cent national average?

Stay tuned for March 2025, when the Sun will have addressed these questions in a way that contributes meaningfully to the discussion.

Johsua Sharf is a senior fellow in fiscal policy at the Independence Institute, a free market think tank in Denver.