A Republican-sponsored bill in the Colorado legislature would likely let state government keep more of your tax money whether it needs it or not.

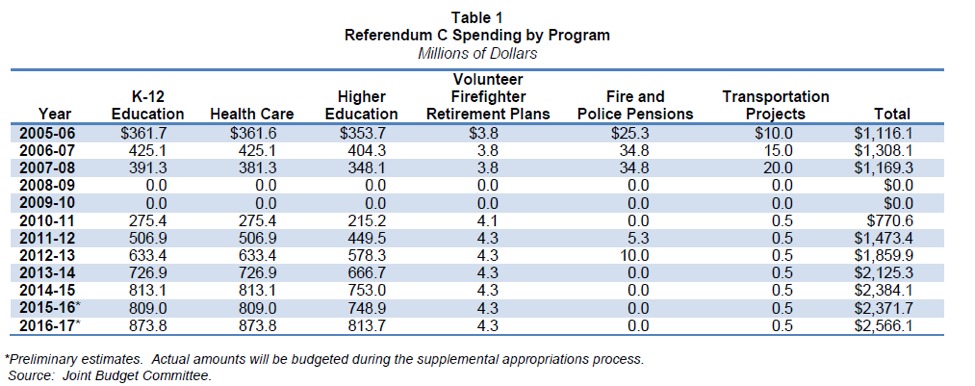

In 2005, Referendum C suspended Colorado’s constitutional limit on the amount of tax revenues that the state could keep. Called the “TABOR timeout,” the Referendum allowed the state to reset the limit on state revenue collection at the highest amount of annual revenue received between June FY 2005-6 and FY 2009-10. Referendum C was a permanent tax increase. As the table below shows, it has increased Colorado state spending by an estimated $2.6 billion over the last decade. At present, only 38 percent of state spending remains subject to TABOR.

Now the tax and spend coalition wants more.

Now the tax and spend coalition wants more.

Some state officials are understandably delighted by any measure that relieves them of the drudgery of running the state on a tight budget. It is much less taxing to be a state legislator when revenues are rising than when they are falling. When spending must be cut, difficult choices are required. No one is happy.

In 2005, the prospect of new Referendum C revenues let officials look forward to a big new pot of money that could be spent to make new friends, benefit some constituents, and satisfy a variety of interest groups. Thanks to the Great Recession, Referendum C did not bring in as much revenue for state government as supporters had envisioned. Growth in state tax revenues promptly slowed from a 14.7 percent increase in FY 2005-6, to 6.4 percent increase in FY 2006-07 and a 3 percent increase in FY 2007-08. Tax revenues fell in the next two years.

Thou![]() gh they were disappointed, Referendum C supporters soldiered on, happily spending the new money on everything from Medicaid coverage for healthy college students, to refrigerator magnets listing someone’s idea of healthy snacks, and subsidies for businesses making solar-powered hydroponic plant pots and hemp adobe. They bought purple buses for Bustang, a state owned intercity bus service that unfairly competes against existing private companies, loses money, and carries fewer passengers in a year than a lane of interstate highway does in a day.

gh they were disappointed, Referendum C supporters soldiered on, happily spending the new money on everything from Medicaid coverage for healthy college students, to refrigerator magnets listing someone’s idea of healthy snacks, and subsidies for businesses making solar-powered hydroponic plant pots and hemp adobe. They bought purple buses for Bustang, a state owned intercity bus service that unfairly competes against existing private companies, loses money, and carries fewer passengers in a year than a lane of interstate highway does in a day.

Now that the Referendum C revenues have been spent, the apparent plan is to raise more revenue by changing the definition of the Referendum C revenue cap. The cap currently increases by the percentage increase in state population plus the rate of inflation. House Bill 17-1187 would grow state spending by the increase the average annual change in Colorado Personal Income over the previous 6 calendar years.

The Personal Income in the bill is not what you report to the IRS. It is an estimate of an accounting category in the US National Income and Product Accounts. Produced by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, it reflects the income received by individuals. It includes wages, rents, interest, dividends, business income, pensions, and estimated government transfer payments from programs such as Social Security, Medicaid, and Medicare. It does not include the taxes you owe. If your taxes go up to pay for a bigger Medicaid program, Colorado Personal Income goes up even though you personally have less money to spend.

Personal Income measures how much people work, save, and invest. It does not measure how much it costs to run state government. If someone in Colorado puts in overtime at his job, state tax revenues and average Personal Income rise. The cost of providing existing government services remains the same. Why should the state get to spend more simply because someone works harder?

Under House Bill 17-1187, the Colorado Legislative Council Staff predicts that TABOR tax refunds will fall by over $300 million in the next two budget years, taking roughly $200 extra from every family of four and giving it to the legislature to spend.

Tying the cap to Personal Income might even end up increasing government waste. If tax rates and subsidies are the same, sustained increases in Personal Income generally mean individuals have higher incomes. People with higher incomes need less government subsidized income support, child care, and Medicaid so state government should spend less. With a cap pegged to Personal Income, it will keep spending more.

Increasing state spending as population grows assumes that larger populations require more government services. This may not always be the case, but it at least refrains from taxing people simply because they work harder. It is also less likely to take money from productive private sector uses so that state bureaucracies can buy refrigerator magnets, grow pots, and purple buses.

Linda Gorman is an economist with the Independence Institute, a free market think tank in Denver.