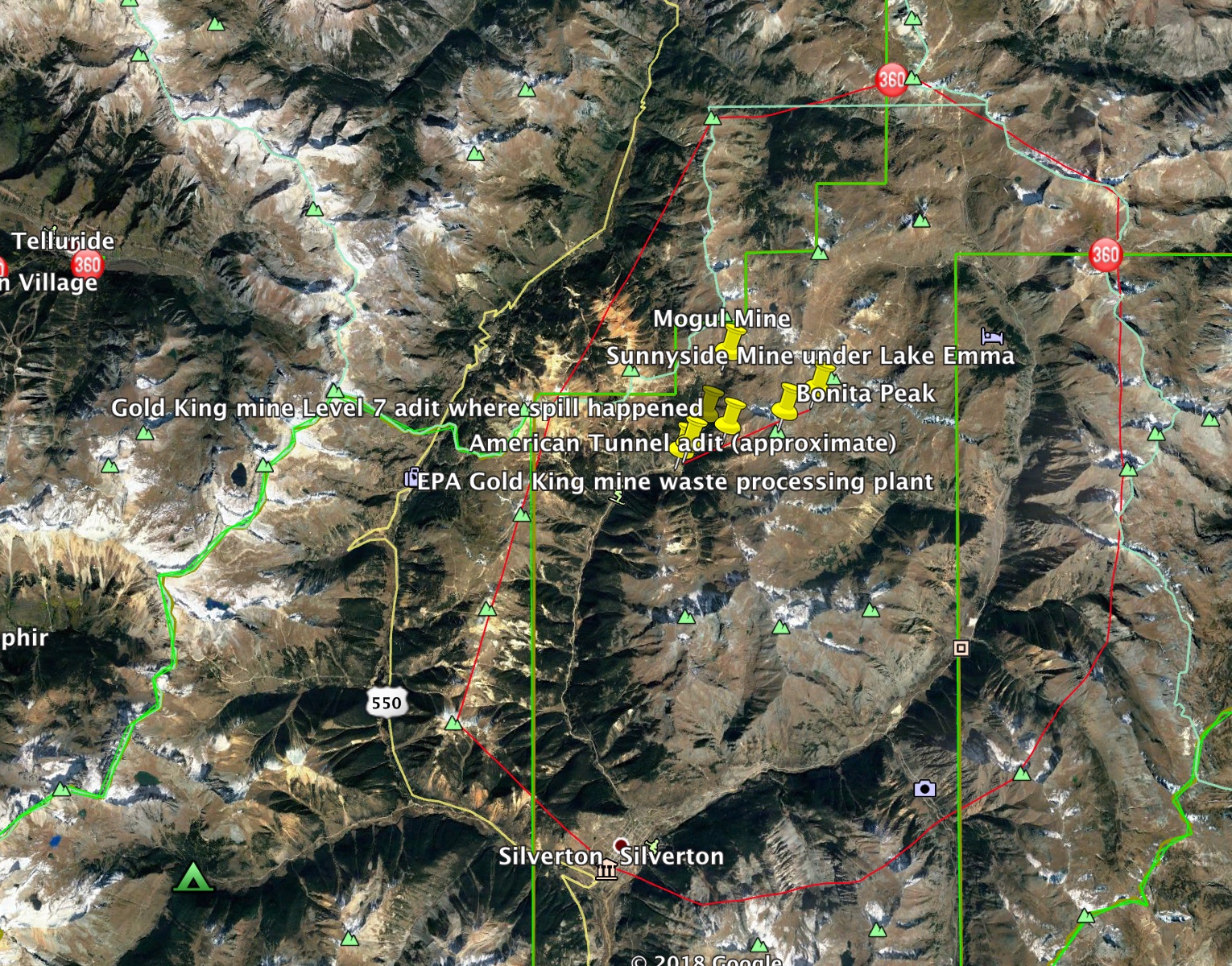

In 1991, after more than 140 years of mining activity, the Sunnyside mine, the last major mining operation in Silverton, Colo., closed down. In its heyday Silverton produced two million ounces of gold, 51 million ounces of silver and hundreds of millions of pounds of copper, zinc and lead from the enormous collapsed San Juan volcanic caldera.

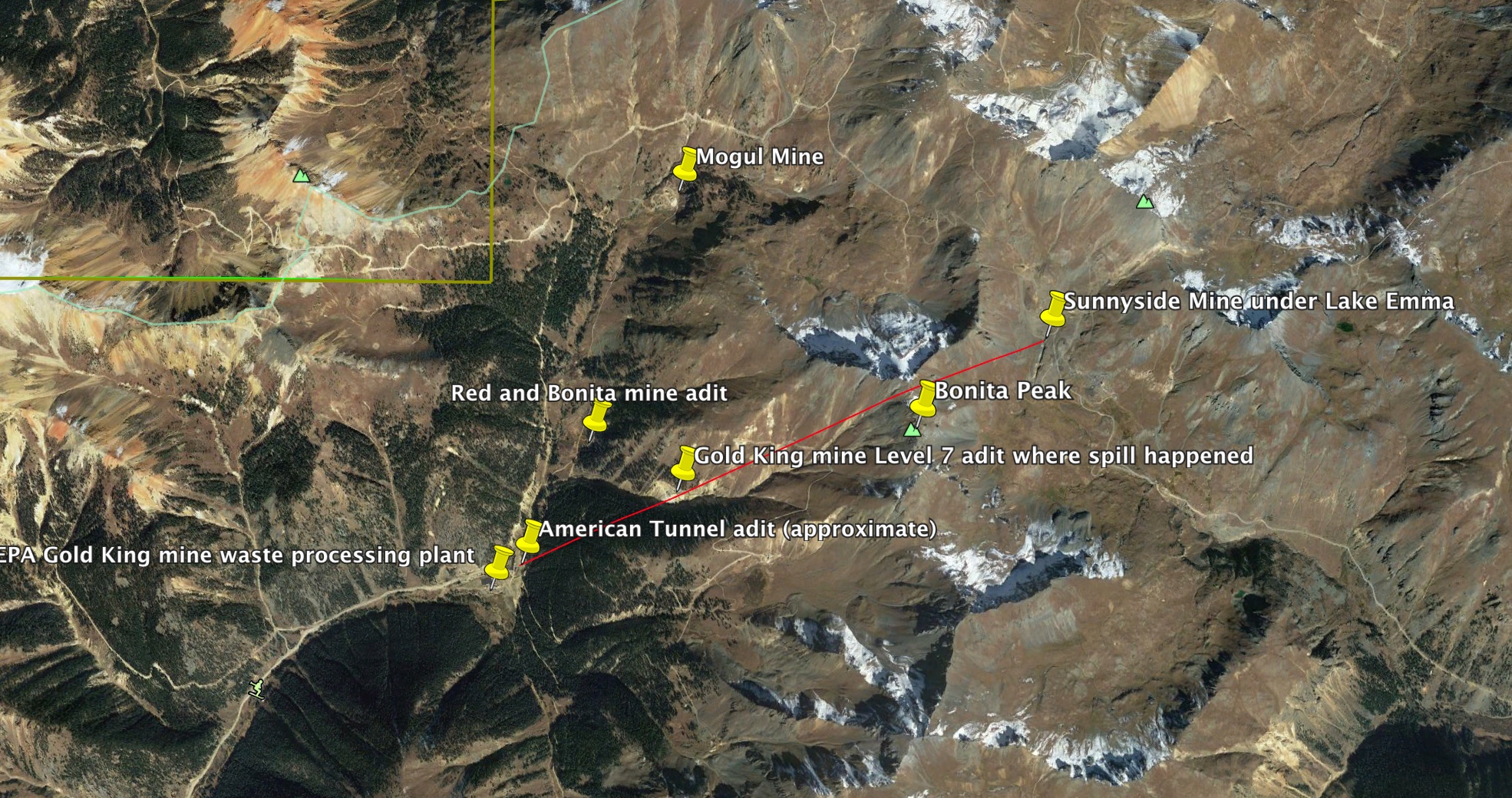

On August 5, 2015, contractors working on a mine-waste drainage remediation project for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) breached the plug in a tunnel at the entrance to the 7th level of the Gold King mine on Cement creek, above Silverton, Colo.

The pressure of an estimated three million gallons of water laden with metals including mostly iron, but also lead, aluminum, zinc, and cadmium blew out the plug installed in 2003 and poured down Cement creek into the Animas river, creating a plume of yellow-orange water that panicked residents as far away as New Mexico and Utah, but which was quickly diluted and according to EPA chemists was never toxic to humans. View an animation of the Gold King Mine plume

![By Riverhugger [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](https://pagetwo.completecolorado.com/wp-content/uploads/Animas_River_spill_2015-08-06-small.jpg)

Photo courtesy of Riverhugger

How did the blowout happen?

To understand the blowout one must know a few facts. First, a column of water one foot tall creates 0.433 pounds per square inch (psi) of water pressure at the bottom of the column.

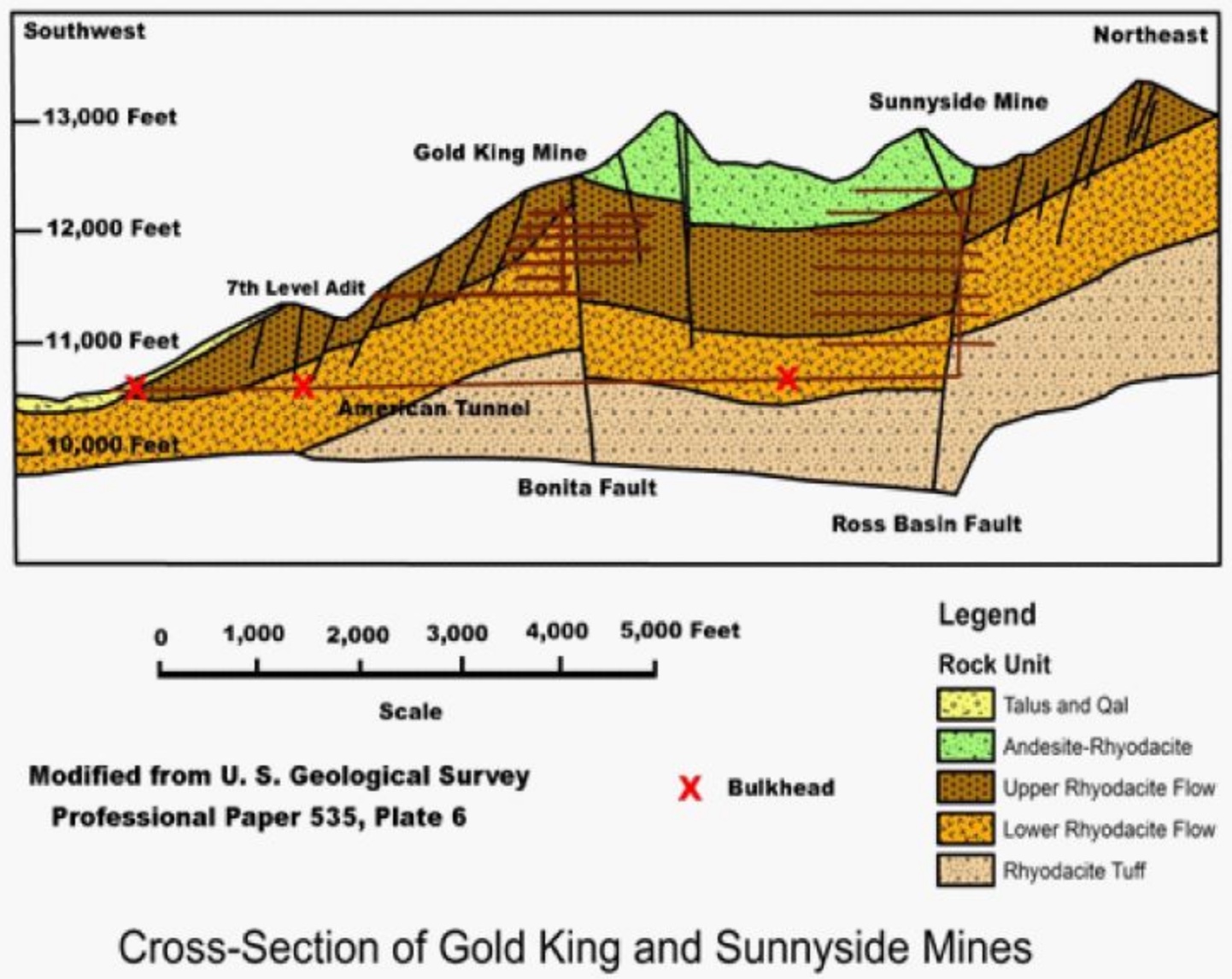

Second, the original find, or strike, of the Gold King mine was discovered high above Cement Creek, at more than 12,500 feet above sea level. By the time the mine closed in 1923, seven levels of tunnels, each 100 feet below the other, had been constructed inside the mountain. The 7th level tunnel, called an “adit,” is the lowest opening to the surface.

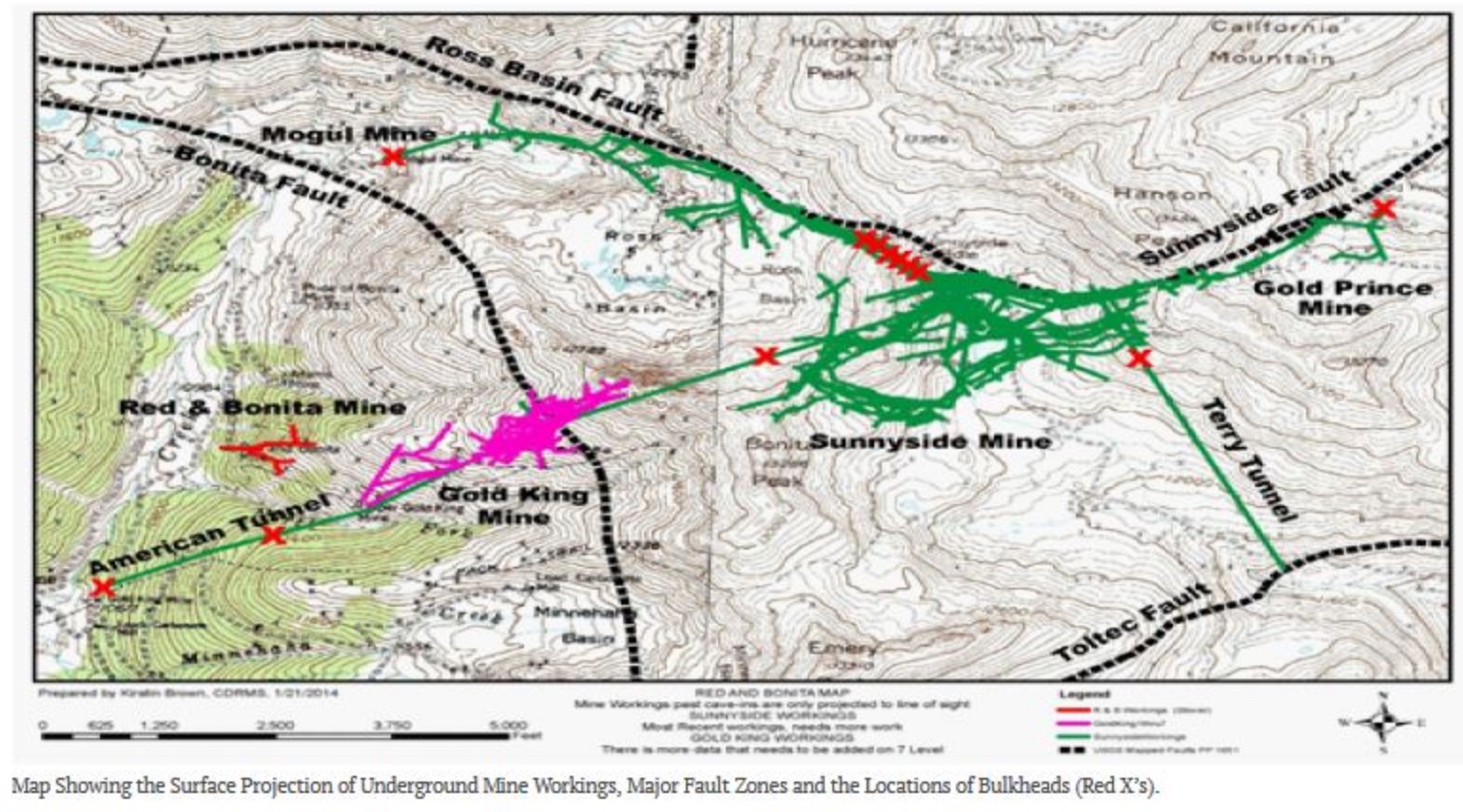

But above, below and beside the Gold King mine are the Red and Bonita mine, the Sunnyside mine and the American Tunnel, a tunnel bored below the Gold King 7th level from the Cement creek drainage more than a mile and a half into the mountain to allow ore from the Sunnyside mine to be hauled out and transported to a mill.

The mountains around Silverton are riddled with more than 400 mines, some of them, like the Gold King and Sunnyside mines having dozens of miles of tunnels on many different levels. No one knows exactly how many miles of tunnels burrow through the district, but Beverly Rich, Chairman of the San Juan Historical Society said that the society archives contain “literally at least 10,000 mine maps” of the area.

How did the EPA screw up?

EPA officials claimed that they were unaware of the high water pressure inside the mine, but an August 2015 internal EPA review of the spill said that signs of pressure and the water level were all there. One of the bits of evidence that didn’t register with crews is that after three bulkheads were installed in the American Tunnel to stop leakage, water begin pouring out of the adjacent Red and Bonita mine in 2006. The bulkheads were put in place by Sunnyside mine owner, Kinross Corp. of Canada as part of a voluntary remediation effort that was approved by the EPA.

After the bulkheads were closed the water level in the Sunnyside mine rose 1,071 feet, according to a 2017 report by Technical Assistance Services for Communities, a consulting company hired to independently investigate the spill. “After mining, the groundwater levels are thought to be approximately 11,500 feet above sea level along the American Tunnel, above the Red and Bonita portal elevation of 10,957 feet and Gold King portal elevation of 11,436 feet,” says the report.

Applying the weight of water to the maze of tunnels that hydrologically connects to the 7th level adit, it’s possible for water pressure to rise as high as 466 psi at the American Tunnel adit.

The report says that water pressures as high as 450 psi were used in calculating bulkhead installations in the American Tunnel.

The EPA knew of the risk of high pressure water in the Gold King mine as early as June, 2014 but decided it was too expensive to drill a small hole through the rock beside the adit to check the pressure, something operating mines have been required to do since a 1911 iron-mine flood disaster near Hiburnia, NJ caused when the wall between a flooded mine next to the New Langdon mine was accidentally breached by a mining blast, killing 12 miners.

When contractors began disturbing soil at the mouth of the adit, an unknown amount of water pressure behind a wooden bulkhead backed by a pile of dirt quickly burst the blockage and three million gallons of highly concentrated mine waste flowed out. One of the workers noticed a tiny high-pressure spray of water coming out of the rock above the tunnel, and within minutes the water destroyed the bulkhead and raged downstream for 9 hours.

Old-timers saw it coming

Old-timers in Silverton have faulted the EPA for approving remediation efforts like the bulkheads in the American Tunnel without clearly understanding hard-rock mines or mining.

Larry Rabb, a long-time Silverton resident who worked underground in the American Tunnel for Standard Metals, a predecessor owner of the Sunnyside mine, scoffed at the EPA’s efforts to deal with acidic mine drainage. “Everybody who’s worked underground knows what happens when you block mines from draining,” he said. What happens, according to Rabb, is that the water backs up in the mine and eventually finds a way out.

Graphic courtesy of David Briggs and Geomineinfo

That’s exactly what happened. Between the bulkheads in the American Tunnel built between 1998 and 2002, other bulkheads in the system and the collapsed Gold King mine 7th level opening, water filled the mines and moved through cracks and fissures in the rock, eventually flowing out of the Red and Bonita mine, whose opening is at 10,893 feet. Then the EPA tampered with the fragile Gold King mine plug. The resulting flood of mustard-colored water became a worldwide news sensation.

So now, like Hans Brinker, the fictional little boy with his finger in the dyke that saves Holland, the EPA is in the position of trying to stick metaphorical fingers in a poorly-understood network of mine openings and natural fissures that allow water to leak from tunnel complex to tunnel complex inside the mountain. The higher the water level in the mines rises, the higher the pressure, which results in more leaks springing up in unpredictable places.

What is the EPA doing now?

Faced with the task of plugging leaks created by plugging leaks that caused the Gold King blowout and figuring out how to process all that water to make it clean enough for fish, the EPA is now trying to force the Sunnyside mine owners to do the heavy lifting of figuring out how the water gets from place to place inside the mountain.

On March 15, 2018, the EPA “issued a unilateral administrative order to Sunnyside Gold Corporation to conduct groundwater investigation activities at the Bonita Peak Mining District Superfund site.” This order could potentially cost the company tens of millions of dollars.

Why the EPA is now attempting to burden Sunnyside Gold with figuring out the hydrogeology of a problem the EPA caused by approving tunnel bulkheads to hold back the water as an approved remediation method rather than simply continuing to process the effluent is unclear.

In a March 15 article in the Denver Post, Sunnyside Gold Corp. reclamation operations director Kevin Roach said, “Sunnyside is not the cause of water quality issues in the Animas River and its activities in the area, including spending $30 million on reclamation over the past 30 years, have resulted in less metals in the Animas basin than would have otherwise been the case.” “We are hoping that our remaining assets can be efficiently utilized in timely, proven and effective solutions to improve water quality rather than pointless studies or litigation,” he continued.

One of the little-known facts about the mining district is that so many metals lie exposed to surface weathering that creeks in the area were declared “undrinkable” as early as 1874 due to natural contamination. The EPA has yet to quantify what part of the metals found in the Animas river are caused by mine waste and what are naturally-occurring leaching.

Claiming that the EPA is more concerned about fish than people Rabb said, “Even the Indians didn’t drink the water from some rivers. The word ‘uncompaghre’ in Ute means ‘stinking water.’”

Treatment removes tons of metal

After the spill the EPA built a treatment plant at the bottom of the gulch below the Gold King mine adit. The drainage from the adit, some 600 gallons per minute, flows through a pipe to the treatment plant. Another estimated 160 gallons per minute still flows from the nearby American Tunnel, in spite of the three interior bulkheads. That water currently goes untreated directly into Cement creek. An unknown amount of seepage through the rock also ends up in the creek.

According to Angela Ledgerwood, Response Manager for the treatment plant, who gave Complete Colorado a brief tour of the facility, the waste is circulated through a system where lime is added to reduce the acidity of the slurry and clarifying chemicals are added to aid precipitation of suspended metals.

The water is then pumped into giant semi-permeable bags sitting in lined pits. In the bags the metals precipitate out, sinking to the bottom of the bag and the clarified water seeps out of the bag into the lined pit, where it is pumped back to the plant to be recirculated again and again until it meets the required purity standards. Then it is diverted through a pipe into Cement creek.

The sludge trapped in the bags continues to accumulate until each bag is more than six feet thick. The plant produces about 4,600 cubic yards of sludge per year. The full bags are cut open and the sludge is transferred to another lined pad to dry. Then it is loaded and transported for storage.

Until a few weeks ago the dried sludge was stored in a large pit near the plant. The EPA has been searching for a permanent home for what it says is non-toxic sludge made up primarily of zinc, lead, aluminum and iron. No mention has been made of the viability of reprocessing the sludge to extract the metals for commercial use rather than simply stockpiling them forever.

In late May the EPA identified a mine tailing dump near the Kittimac mine along the Animas river a few miles northeast of Silverton as a potential disposal area. The EPA secured an agreement with the landowner to stockpile the sludge there. The sludge will be mixed with existing tailings, which according to the EPA will help to permanently bind the metals in place and reduce further leaching. Transport is set to commence in June.

Silverton residents are glad to see an interim solution for storing the sludge but have concerns about the impacts on the tourist trade from the heavy trucks that have to pass through town to get to the disposal site. The EPA has promised to mitigate both traffic and dust problems during the transport.

The $20,000 weekly cost of ongoing water treatment for the Gold King mine will most likely need to continue forever if water quality remains a top concern. Remediating and treating all the mine waste in the area appears to be an extremely expensive long-term idea that benefits fisheries but cannot mitigate the effects of natural weathering in the highly-mineralized San Juan caldera where Silverton’s mines are located.

Update:

Complete Colorado requested contact from the EPA during the visit to the Gladstone treatment plant. No response was received by press time.

The Environmental Protection Agency responded June 27 requesting several corrections, which Complete Colorado has reviewed.

EPA: “The Gold King Mine discharge was on Aug. 5, 2015 (not Aug. 15).”

An error in the date of the spill was corrected from Aug. 15 to Aug. 5.

EPA: “No trucks are going through Durango or Silverton.”

An incorrect reference to Durango in the next-to-last paragraph was changed to Silverton.

Any hauling from the treatment plant to the new disposal site necessarily passes through the northeast end of Silverton because there is only one road out of the Cement creek canyon and one road up the Animas valley to the disposal site. These roads intersect within the town limits of Silverton.

EPA: “EPA did not approve the placement of bulkheads in the mining district and in the American Tunnel.”

Bulkheads were put in place after the closing of the mine and tunnel as part of Sunnyside Gold’s voluntary remediation efforts during the time that the EPA was working on mine waste remediation in the district. Statements by locals and newspaper reports indicate that the EPA was actively involved in remediation consultation with mine owners and was at a minimum fully aware of the bulkhead installations. Therefore, Complete Colorado concludes that even if it did not formally approve the bulkheads, it tacitly did so by not prohibiting or objecting to them during their consultations. Complete Colorado concedes that it has no official documents from the EPA approving those bulkheads.

EPA: “There wasn’t a bulkhead in the Gold King Mine at the time of the discharge.”

In this EPA photo, taken Aug. 5, 2015, the remains of a timber bulkhead can be clearly seen. The mine adit was reportedly both partially collapsed and plugged with dirt bulldozed into the opening both inside and outside of the timber bulkhead years earlier.That plug is what allowed water levels to rise and create enough pressure to blow out the blockage. Seepage from the adit was being treated with three settling ponds constructed by the EPA at the time of the blowout.

EPA: “EPA is evaluating long-term options and solutions for sludge management. We recently secured an interim solution for safely transporting and managing sludge from the plant through this year and are currently evaluating longer-term solutions, including a repository.”

A correction has been made to replace “permanent” with “interim” in the next-to-last paragraph.

EPA: “EPA did not drill into the mine pool because of technical and safety concerns, not because it was too expensive.”

Statements to Complete Colorado by local residents and miners who asked not to be identified out of fear of possible retaliation by the EPA, dispute this claim. Complete Colorado concedes that there may also be technical and safety concerns that factored in to the decision not to determine the Gold King mine’s water level prior to tampering with the adit plug.

EPA: “As has been reported previously, ongoing treatment costs are approximately $20,000 a week.”

A correction has been made to the final paragraph.

Below is an excerpt of the cover letter from Rich Mylot of the EPA:

“EPA is working closely with state and local partners, potentially responsible parties, and the citizens of San Juan and La Plata counties, to make sure that the remedial actions taken at the site are informed by sound science and technical information. Mr. Weiser’s article underscores the importance of this science and information in referencing the mining district’s history and the scale and complexity of the water quality concerns we are confronting. We need to understand how the water system works, and the context and contribution of sources throughout the basin, before jumping to expend resources on actions that may or may not be effective and part of meaningful, long-term, big picture remedies. To that end, the completion of various site investigations and risk assessments at the site is critical; those documents will provide the basis for identifying long-term water quality solutions.”

This statement does not address the rationale or legal basis for the “unilateral order” burdening Sunnyside Gold with the cost and responsibility of educating the EPA on “how the water system works.”