At a Nov. 14 Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) meeting in Silverton about the Bonita Peak Superfund site, Project Manager Rebecca Thomas addressed about 100 people to review the EPA’s accomplishments of 2018 and to “set goals” for the future.

The EPA has been involved in remediation efforts in the area as far back as 1991, leaving residents wondering why the EPA is proposing to go far beyond what has already been in process for decades: improving water quality in the Animas River.

The public relations disaster that ensued after the Gold King Mine blowout on August 5, 2015 kicked Silverton into the limelight as people across the world watched the mustard-yellow slug of contaminated water flow down the Animas River. The public outrage at the EPA’s role in causing the disaster resulted in the EPA quickly declaring the area a Superfund site, generally over the objections of the residents. The EPA had previously declined to designate the area as a Superfund site in 2008, deciding to work cooperatively with stakeholders.

![By Riverhugger [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](https://pagetwo.completecolorado.com/wp-content/uploads/Animas_River_spill_2015-08-06-small.jpg)

Photo courtesy of Riverhugger

But it’s gone far beyond water quality now. One of the results of the Superfund designation is that the EPA has undertaken a broad investigation of possible hazard to human health or wildlife that might result from more than 140 years of mining in the district.

As an example, according to local residents, EPA technicians were seen this summer driving off-road vehicles around the 4-wheel drive trails of the famous Alpine Loop, while wearing full hazmat gear and respirators, to gather dust samples to find out if local off-road guides are at risk.

What exactly the EPA plans to do about those hazards and what the conditions for declaring victory are is unclear. At the meeting Thomas said, “I think that’s not just for EPA to decide, but for stakeholders to decide. We’ve got water quality considerations, we’ve got human health considerations and we’ve got ongoing potential for blowouts as well in the mining district.”

But the stakeholders don’t seem to be in the loop much since the Superfund declaration. When asked at the meeting why some mine waste in Cement Creek is not being treated Thomas said, “That is certainly a criticism and a question that the EPA has heard before.”

The EPA has been hearing that question for more than three years now from community members who are more than a little irked that it has not addressed the most obvious and immediate remediation of mine waste generated by federally-controlled mines and tunnels above the Gladstone plant.

Thomas admitted, “The plant up at Gladstone is very effective, we know how it works, it cleans the water very effectively. It also requires a lot of lime to be brought into the plant and it generates a huge amount of sludge. Managing that sludge is an ongoing problem.”

“We haven’t said no to treating additional sources, it’s something that we need to think about very carefully. A lot of people would like to see us just start treating the water now, as has been done in the past,” said Thomas. “We’re just not there right now.”

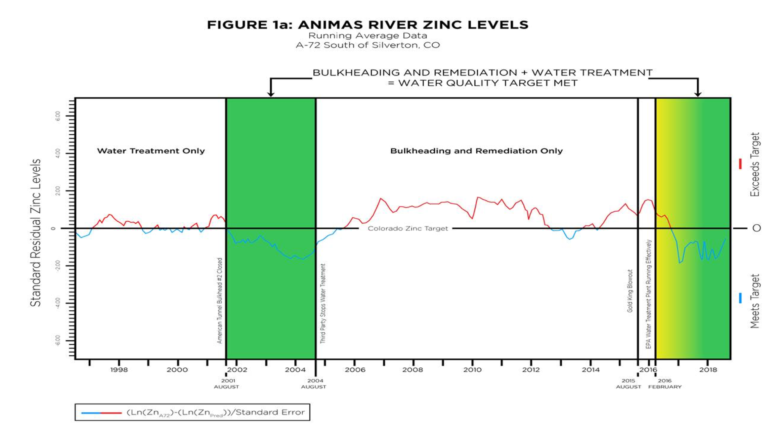

Adding to community frustration over delays, a new analysis of stream data by Steven Lange of the Mountain Studies Institute, an independent not-for-profit mountain research and education center shows that since the Gladstone plant has been in operation, even limited to only processing Gold King waste, water quality in the Animas River just below Silverton has been in compliance with Colorado’s zinc standards since shortly after the blowout. Zinc is used as the indicator metal for water quality assessment by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, which sets water quality targets for the state.

What the EPA is concerned about is money says Silverton resident Kevin Baldwin. At the meeting he, and others at the meeting were critical of the EPA’s refusal to process all of the mine waste above Gladstone.

Thomas’ most telling comment was, “We’re also still in the very early stages of investigating that Bonita Peak groundwater system, so there may be alternatives to lime treatment. We’re hoping we can find some of those alternatives.”

She didn’t elaborate on what those alternatives might be, but at least one popular theory around Silverton is that the EPA’s actual intent is to foist the costs of treating all of the mine waste off onto the Sunnyside Gold Corporation (SGC).

On March 15, 2018, as part of its enforcement powers, the EPA unilaterally ordered SGC to conduct a $5 million drilling and research project in part “to determine the hydrological interconnection of the various underground mine workings.”

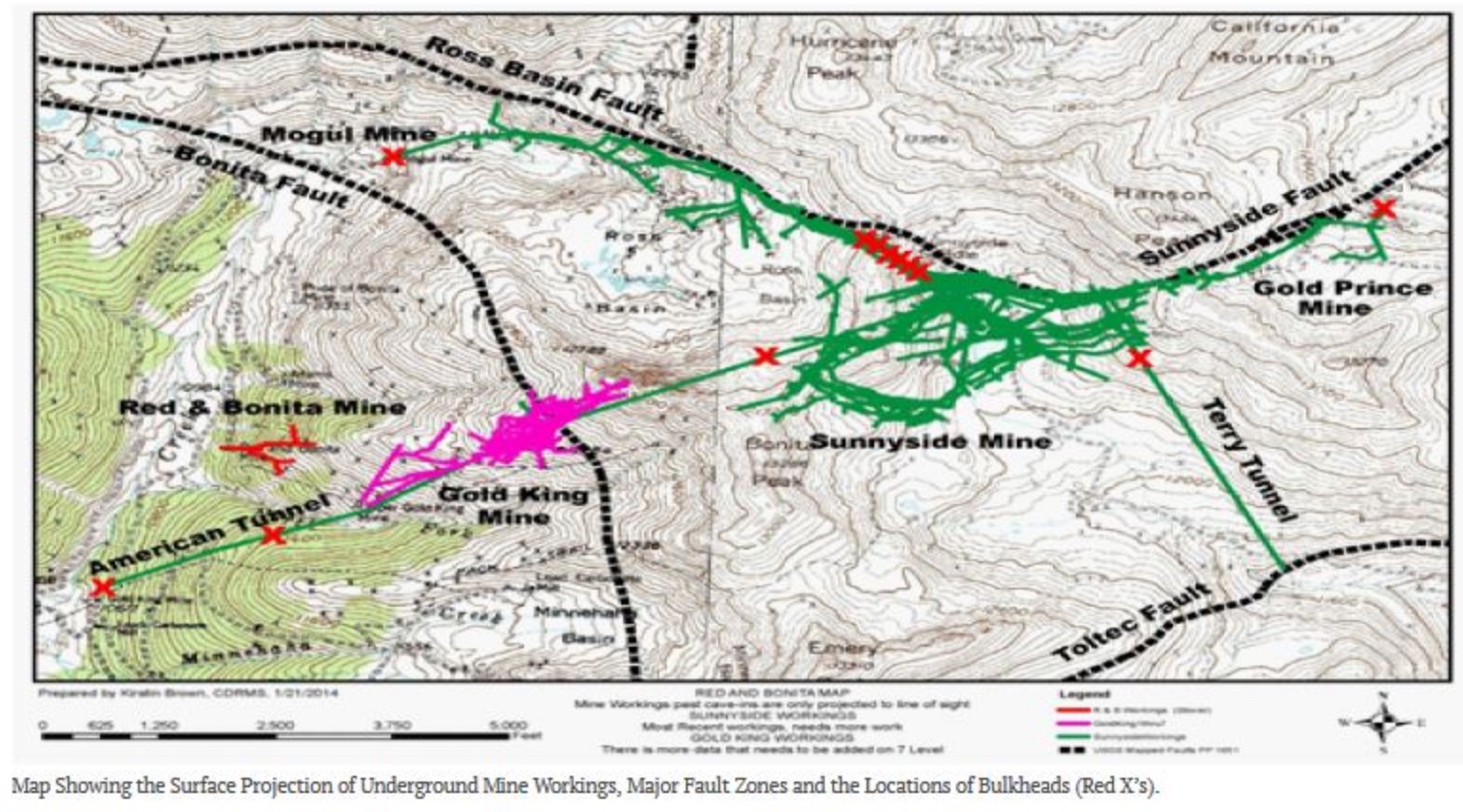

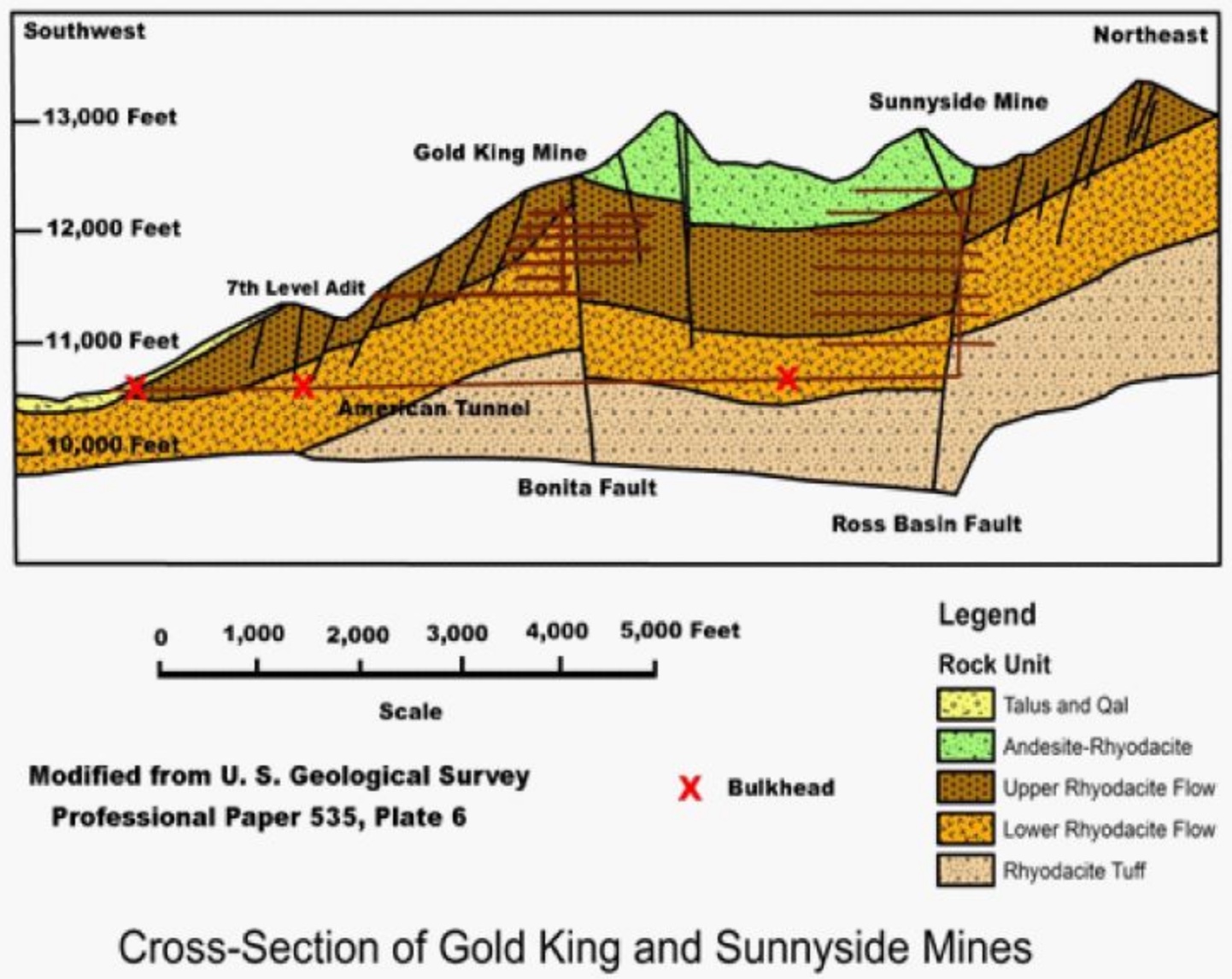

Graphic courtesy of David Briggs and Geomineinfo

The popular theory goes that by claiming that the bulkheading completed with EPA approval in 2004 is causing water to seep through thousands of feet of rock between the Sunnyside Mine and the other mines, the EPA can claim the Sunnyside mine is “discharging” contaminated water into the Gold King, Red & Bonita, Mogul and other mines as well as causing it to flow from springs and seeps that existed long before mining began and dropped the natural water table.

But the express purpose of the bulkheading was to return groundwater levels to an approximation of the natural pre-mining water table to reduce acidification of the water. At the time, bulkheading was the “industry best practice” for remediation and the EPA participated in and lauded both SGC and the state for the work at the time.

Currently the EPA spends $20,000 per month treating Gold King waste, and in 2017 $5,489,000 was budgeted for 3 years of EPA operations in the district.