At current spending levels, what schools do is far more important than how much they spend. Amendment 73 pumps more money into existing school systems. Data from the last 30 years show that the economic damage caused by its higher taxes will likely not be counterbalanced by a significant improvement in student achievement or opportunities.

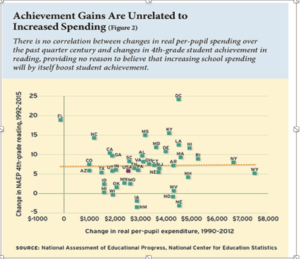

Data from the last 25 years show little correlation between increases in per pupil spending and increases in 4th grade reading performance. As Figure 2 shows, Colorado schools are already reasonably efficient compared to the national average as they have produced slightly above average achievement for a moderate increase in spending. In contrast, Wyoming schools have been rat

her inefficient. The state increased spending by more than $7,000 per student but saw achievement gains that were below average. Florida may have the most efficient schools of all. It reduced per pupil spending and had the second highest achievement gain in the country.

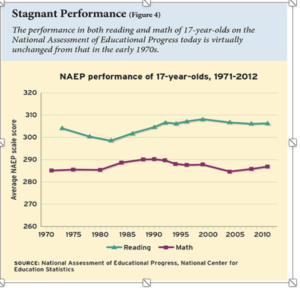

Nationwide, student achievement test scores peaked around 1967. Over the last 50 years, falling class sizes, massive increases in federal spending, and constant classroom experimentation have done little more than return National Assessment of Educational Progress scores to the levels that sparked such concern in the 1970s (see figure 4). In Kansas City in the early 1990s, virtually unlimited funds failed to improve student achievement even though the school district operating budget increased from $3,906 per student to $13,733 per student over 7 years.

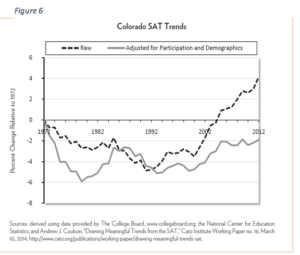

By 2012, Colorado results for the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) mirrored the results from the NAEP. Despite rapidly rising school spending, student achievement on the SAT had yet to reach the level that prevailed in the early 1970s.

During the years shown in Figure 6, the SAT was taken voluntarily by a self-selected group of high school juniors and seniors who wished to attend selective colleges. As of 2017, it is required of all Colorado high school juniors.

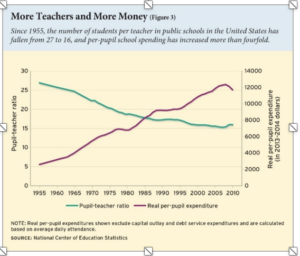

Amendment 73 proponents maintain that the extra tax money will purchase smaller classes. As Figure 3 shows, smaller class size has not had much of an effect even though it substantially reduces teacher workloads. Inflation-adjusted US school spending has increased from $2,000 per pupil in 1955 to $12,000 per pupil in 2010.

Linda Gorman is an economist at the Independence Institute, a free market think tank in Denver.