A May 20 report by Moody’s Analytics comparing states’ fiscal readiness for the next recession contains some sobering news for Colorado. Most states, including Colorado, fall into the “Moderately Prepared” category. Nevertheless, some measures of preparedness are waving yellow flags at us, as we hover close to the “Weaker” category. Policy-makers would do well to heed those warnings before taking steps that could make things worse.

Moody’s breaks down a state’s preparedness into four components – revenue volatility, coverage by reserves, financial flexibility, and pension risk. Colorado falls into the Moderate rating in each component.

Revenue Volatility

Greater revenue volatility makes the state’s income more vulnerable to a recession.

Colorado has some of the most volatile state revenue in the country, according to both Moody’s and an ongoing tracking analysis by Pew. Moody’s measures volatility by the greatest one-year decline in revenue since 2000. For Colorado, that number is 12%, ranking the state 18th, but only a couple of percentage points away from earning a Weaker rating.

Colorado has some of the most volatile state revenue in the country, according to both Moody’s and an ongoing tracking analysis by Pew. Moody’s measures volatility by the greatest one-year decline in revenue since 2000. For Colorado, that number is 12%, ranking the state 18th, but only a couple of percentage points away from earning a Weaker rating.

These results are slightly kinder than the Pew rankings, which place Colorado as the 6th-most volatile. Using data from the last 20 years, the average state’s revenue fluctuates within 5.0% of its overall growth trend; Colorado’s fluctuates up to 8.4%.

Coverage by Reserves

Many states have some sort of reserve fund or other available resources to draw on when revenues decline. Moody’s took the maximum decline from revenue volatility for a given states, and compared it to the size of the reserves available to fill the hole.

Colorado barely edges into a Moderate rating here, with reserves sufficient to cover half of its maximum decline. That makes it the 11th-most vulnerable state, and only 10% away from a Weaker rating.

Financial Flexibility

As Moody’s measures it, financial flexibility is the ability to respond relatively quickly to a recession. Can the executive branch cut or impound spending on its own? What percentage of total spending consists of fixed costs like debt service or pension requirements? How vulnerable is it to increased Medicaid spending when people lose their jobs?

Here Colorado fares somewhat worse than average. A previous Moody’s study (“Stress-Testing States 2018”) combined both revenue shortfall and increased Medicaid spending into a single fiscal shock number, for both severe and moderate recessions. For a moderate recession, Colorado ranked at the middle with a 2.9% combined shortfall; for a severe recession, it ranked 18th-worst with an 11.0% shortfall. This potential shortfall has been exacerbated by the Medicaid expansion under previous governor John Hickenlooper.

Perhaps surprisingly for a state that nominally forbids general obligation debt and long-term debt obligations without a vote of the people, Colorado ranks in the lower third for debt service and overall debt as a percentage of revenue. According to th![]() e state’s Consolidate Annual Financial Report (CAFR), in a discretionary budget of slightly over $20 billion, roughly $500 million of that is committed to debt service in FY2019. Its total long-term liabilities are slightly more than $29 billion, including pension obligations, which is just below the total budget of $31 billion.

e state’s Consolidate Annual Financial Report (CAFR), in a discretionary budget of slightly over $20 billion, roughly $500 million of that is committed to debt service in FY2019. Its total long-term liabilities are slightly more than $29 billion, including pension obligations, which is just below the total budget of $31 billion.

Financial flexibility is also where Moody’s role as an analyst leads it somewhat astray. It penalizes a state for requiring a supermajority in order to raise taxes. Colorado’s Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights (TABOR), with its requirement for a vote of the people for tax increases, probably earns two penalty points on a scale of 0 to 1.

However, such restrictions also help keep the state government from taking on more fixed spending than it can handle, and the two states most at risk during the next recession – New Jersey and Illinois – famously have no such limitations. TABOR might make it harder to raise taxes on a population with rising unemployment, but it also helps keep a state farther away from trouble in the first place.

Pension Risk

Colorado’s Public Employee Retirement Association (PERA) has long been one of the most under-funded state pensions in the country. Reforms passed in 2018 under Senate Bill 200 probably both help and hurt here. The plan remains underfunded, but allows for benefit cuts and increased employee and employer contributions in the event of lower-than-expected returns. However, it also bakes a $225 million line item into the state budget, counting as a fixed cost and reducing overall financial flexibility.

Recession Risk

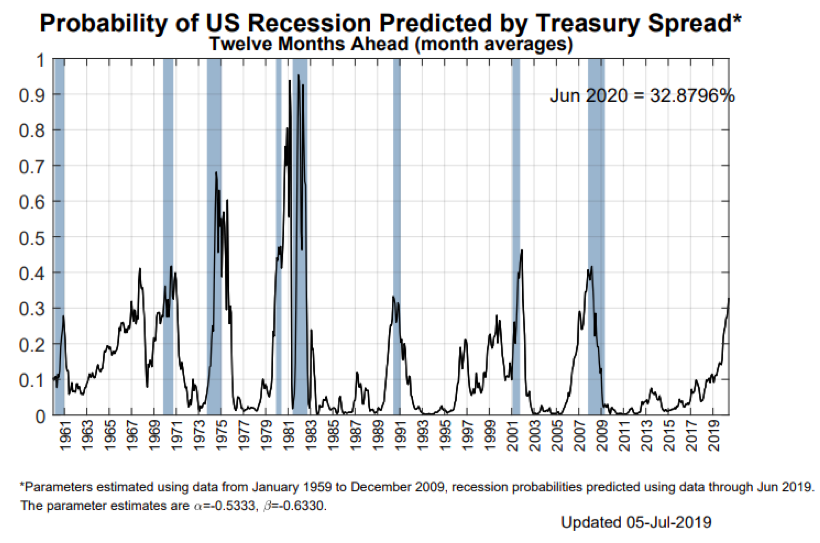

This news comes at a bad time. For one thing, the risk of recession is rising, and one may be on the way sooner rather than later. (If the suspension of the Trade War with China can redirect resources back to economic growth, so much the better.) The chart below shows the risk of recession as measured by the New York Fed at the spread in Treasury Rates. With the exception of 1968, every rise to this point since 1960 has been followed by recession.

It is the job of state governments to prepare for that eventuality, not to ignore it by assuming that the good times will continue forever, but there are few signs that Colorado’s government is alert to the danger.

Part of the problem may lie with the state’s forecasting arm at Legislative Council. It’s not that the economists there are particularly bad at forecasting. On the contrary, they’re probably as good as anyone can be. But as Nassim Taleb remarks in The Black Swan, even the experts, especially the experts, are terrible at forecasting.

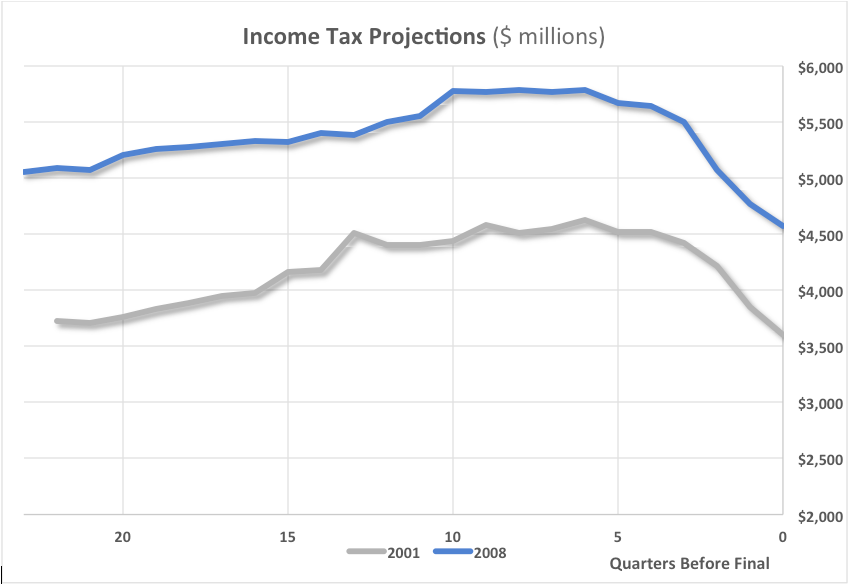

Below are the Legislative Council’s quarterly revenue projections preceding the last two recessions in 2001 and 2008:

The final numbers, the 0 date, are at the end of the fiscal year in question. Notice that even up to a year before the recession’s fiscal year, Legislative Council is still projecting rising income tax receipts. They don’t begin to significantly decline until the fiscal year is underway.

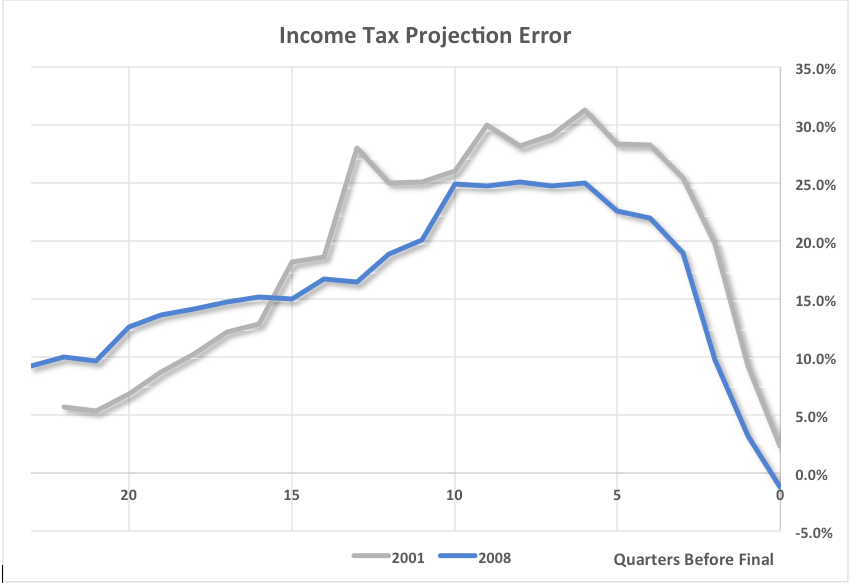

Here are the same numbers as a percentage error:

Even as the fiscal year begins, Legislative Council is still overestimating income tax revenue by about 25%. This isn’t overall state revenue – excise taxes, fees, and sales taxes are less volatile, and federal inputs can be financed by debt. But they’re still wildly inaccurate well past the point where budget decisions have already been made and passed into law, and they’re the primary forecasting tool used by the legislature in making those decisions.

Joshua Sharf is a fiscal policy analyst at the Independence Institute, a free market think tank in Denver.